Issue 12

—Autumn 2020

Human

Barbara – A Tale of Transformation

I am 12 years old

My parents like to take me on cultural trips. They strive to broaden my horizon by taking me to explore other cultures around the world. We use school vacations to travel, usually to Europe and America, since we can’t really afford to visit places further away. Places, which would most probably challenge my worldview on a much deeper level.

For this winter break we’ve travelled to Barcelona. Me and my father share a bench in front of the Sagrada Famílía by Gaudí. Spring is here, still and calm. We could feature in an insurance company ad, sitting on the bench like this. I eat ice cream – my father sips a cappuccino from a paper cup.

My father has a way of informing our conversations with small lessons for me to learn, so that I barely notice. I suspect him of planning these weeks before.

“Enjoying your ice cream?” my father asks.

“Yes,” I answer.

“Which flavour did you get?” my father again.

Me: “Strawberry and chocolate.”

“Ah, your favourite flavours?” A father’s desperate attempt to fuel a conversation with his

twelve-year-old daughter.

“Yes.” I reply.

We sit together in silence…

“Do you want me tell you a story?” my father asks. I nod in approval with my mouth full; I love to blend the flavours together in big chunks of strawberry and chocolate.

“This church in front of us is called Sagrada Famílía, designed by Antoni Gaudí who was an architect. He was obviously a very ambitious architect – he saw the construction of his church begin in 1882, while it is estimated that it will only first be completed in the year 2026!” My father stresses “twenty & six!”

“…Or 144 years from the start of its construction. Gaudí’s experimental new building methods and innovative use of architectural forms have made the building extremely complex to build. However, in recent years it has become easier and easier to manifest Gaudi’s vision into reality with support from computer programs and new building processes…”

My father looks at me and, as our eyes meet, I can feel that he senses that I am looking through him. My father stops speaking for a while and takes a sip of his coffee…

He then carries on. “But this is not the story. The story is about when Salvador Dalí, one of the surrealist artists, was showing Gaudí’s church to the architect Le Corbusier who was a modernist…”

My father looks at me again; he sees that I am still staring through him…

“Dalí, remember?” my father asks and then continues, “…the artist who felt so bad for his cat, because the cat was not allowed with him on his travels between countries. Well, he decided to eat his cat so that it would travel with him – in his stomach?” I finally relate a bit and laugh nervously.

“…and Le Corbusier, the man who is responsible for so many middle-class people wanting to live in square, concrete houses with big windows. One of the main guys to develop modernism?”.

“Ummhumm…” I answer half interested.

My father continues: “So Dalí was showing Gaudí´s church to Le Corbusier. Of course, Le Corbusier was appalled by what he saw. The church, by his standards, was a very poor piece of architecture. Le Corbusier got all worked up and proceeded to give Dalí a lecture about the perfect form of architecture in relation to modernism as a philosophical guideline. Dalí listened patiently and waited for Le Corbusier to finish his preaching. After a short while, Dalí answered firmly:

‘No, architecture should be soft and hairy!’.”

I am 19 years old

I find myself in front of the mirror in my bedroom, pulling on tight jeans, T-shirt and socks. I observe how the cut of those material blobs interact with my body and contemplate what I am signalling to society by wearing these materials, these cuts and these colours? There are piles of clothes scattered around my room, some dirty – some clean. Perhaps, it is time to use the washing machine and tidy up the room? In addition to the extreme quantities of clothes in the room, there are some books lying around, their titles denote material culture, cultural theory, fashion and style; Cradle to Cradle, The Story of Waste and This Changes Everything, all carrying a label from the public library. On my nightstand, there is a stack of magazines, on top the last issue of The Economist, borrowed from dad. The headline reads “Endless Conflict?”

This T-shirt is new. I reach over my shoulder for the white silky label, tearing it away from the cotton fabric. I pull at the T-shirt to adjust it to my body; the cotton is soft and stretchy. This cut complements my figure and I feel a brief sensation of self-content, but almost immediately anxiety washes over me and I wonder if the T-shirt will survive even a single machine wash. I know that the fabric is lousy, but how lousy? How long can I enjoy the existence of this cotton shirt? Cotton. I gaze down at my socks; cotton. And a bit higher at the jeans; cotton. The T-shirt; cotton. I am all dressed in cotton. Even my underwear is cotton. I leap onto my bed and pry my laptop open. I go straight to YouTube, in the search bar I enter: “How is it made, cotton t-shirt”. The first video has this exact same title. 8 minutes and 32 seconds. A bit long, but still I click the link.

The video starts, it’s a cliché: A mix of sterile shots showing geography, materials, machines and people. The audio track features a monotonous robot-like voice recounting the history of cotton. Most cotton comes from the US, China, Uzbekistan and India where the cotton plant grows on huge swathes of land before being harvested with the use of gigantic machinery. Once the balls of cotton have been collected, they are transferred in bales to a central factory for sanitation and drying before being shipped off around the world as raw material. Most of the processed cotton bales are delivered to other large factories in China where the cotton is spun into threads. Yet again, the threads are shipped off for distribution to other Chinese and international factories where the threads are used to weave textiles. Ultimately, the textiles are shipped further yet, to other factories around the world that use the textiles for clothes – in my case a humble cotton shirt. A T-shirt.

I look up and find my own reflection wearing this cotton shirt and I think of all the hidden things the robotic voice did not disclose: The production and shipping of the machinery used for the production of the cotton, the construction materials for the factories themselves, all of the working hours, not to mention all of the energy that is required to run this system. Energy, that is mostly fuelled by oil coming from the material remains of living beings that died millions of years ago. My mind conjures up a phantasmagoria of catastrophes; dead animals with their stomachs bloated with plastics, melting ice caps and submerged megacities, the last bee dying…

I don’t want this cotton shirt anymore.

I am 26 years old

I enter the living room and run into my dad. He looks at me in amazement, he is surprised to see me. Not only because I have been abroad for some time, but also because I have changed.

A moment flashes by, my father’s face is transformed, expressing anger and despair. He shouts at me with tears running down his cheeks. I did expect such reactions, but I am still taken aback and shaken. Despite everything that has happened, I am still not sure if I did the right thing.

I find myself standing in the centre of the living room and dad seemingly losing his mind in front of me. I catch a glance of a framed photograph on the bookshelf by the wall behind him. I have often seen it before. It shows dad, somewhat younger, posing in front of food market stalls. The photograph is probably made in Southern France in early autumn. Dad is lightly dressed, wearing a loose linen shirt and shorts, sporting a beautiful moustache and his hair tied up in a ‘man bun’. He holds a large, organically grown tomato that seems to be imploding under its own weight. A close friend sent the photograph to dad for Christmas many years ago. In the corner it reads “Vegan forever xxx”.

I am 22 years old

I am leaving a shopping mall after dark, entering a huge parking lot. An occasional car passes by, the wind howls and I take a step back as the cold hits my face. A yellow plastic bag drifts across the horizon and as my eyes track its movements, I spot a large illuminated billboard at the edge of the parking lot by the highway beyond. I walk closer, but the billboard is so brightly lit that my eyes hurt at first. As soon as my eyes adjust, my ears pick up the slow humming from the spotlights. Hydroelectric power from the highlands, flow of water transformed into electricity, travels hundreds of kilometres across the country and now it emits a low hum across the street, carried over the carpark and into my eardrums.

The billboard features a young woman in her thirties. We only see her youthful face, naked shoulders and chest. Her skin is monochrome and colourless, no signs of birthmarks or scars. Her facial expression is familiar but distant. A symbol for youth and future. Her eyes wide open, stiff and staring into the void. I don’t know who she is addressing, nor what she wants. It is obvious that the image has been digitally retouched, her smile is completely symmetrical, and the two sides of the face mirror one another. In the bottom corner there is a clean and geometric logo: Temper Genetics and below it says: “Transformational Power of the Future”.

I think back to something my dad used to say: “The advertisement is the one true artform of today’s world, there are no other artworks that unconsciously reflect the zeitgeist as well as ads” he says and smirks…

True, in many respects. Moreover, this past decade has been shaped by relentless news reports on biotechnology. Public opinion is polarised, all debates are polemic, and the moralists and the capitalists of the world take turns in screaming at one another on live television.

Once again, we humans have managed, by virtue of science, to excavate Pandora’s box and pry it open. This time, it is genetic technology that allows us to design life itself, directly influencing all systems of the biological world. Recently, there has been breaking news almost every day, telling stories of scientists in far flung places announcing the emergence of new organisms, bacteria, plants and animals. This quest for the holy grail now entails the transformation of the human being itself, both physiologically and psychologically. There is a Wild West within the world of science, with scientists striving to find suitable excuses for genetically modifying new, transformed organisms. Most often, such decisions are made on moral grounds, such as the elimination of diseases, disorders and disabilities. It seems, that science is paving the way towards a better human world.

I am 9 years old

I sit in a chair in a hair salon and my whole body is covered by the hairdresser’s gown. When I look in the mirror, I see a levitating hairy head above the gown. I realise why dad took me to the hairdresser and I feel a little guilty after having nagged so much about it. Further away in my mirrored field of vision I see dad sitting in a white leather couch, poking his phone. Next to him, a woman in her sixties sits staring into the air. She is also dressed in a gown like I, so it is hard to tell what she is wearing, but she wears heavy make-up and sits there, arrested like a statue. Her hair is covered in white foam and in her hair, there are small snippets of aluminium wrap, clasped on with little plastic clips. Her head is half-way suspended in a tubular machine that is hard to know what is supposed to do.

“That make 27.800 ISK”.

The amount catches my attention and in the mirror I catch a glimpse of the hairdresser’s back, she is obviously charging a customer.

“Deep wash and head massage, shortening, colouring, haircut and hairdo, yes that’s it –

27.800 ISK,” the hairdresser repeats.

A youthful lady’s hand with glossy brightly orange-coloured nails appears in the mirror, between her fingers there is a golden credit card. The hairdresser takes the card and slides it through the slot on the machine, I watch her wait for the transaction being approved. “…offer the lady?” I hear my hairdresser say and my focus shifts from the background in the mirror to the foreground. The hairdresser is looking at me with a question in her eyes.

“Sorry?” I say.

“And what kind of haircut may I offer the lady?” the hairdresser asks again…

I am 24 years old

I am in bed, just waking up. Slowly, I open my eyes, accustoming to the light. It is high noon. I’m sure, because of the bright daylight streaming through the windows. I sit up straight and take my bearings, I glance through the window and recall that I am far away from home.

The city stretches beyond my horizon and if I listen closely, I can hear the crowds outside. I want to go outdoors; I have been confined to this small apartment for three weeks and I’m dying to leave but I’m not ready to go just yet. I’ll wait a bit longer. I feel as if I’m hung over, I’ve felt this way for three weeks. This must be about to get better, the doctor told me both physical and mental recovery could take a few weeks.

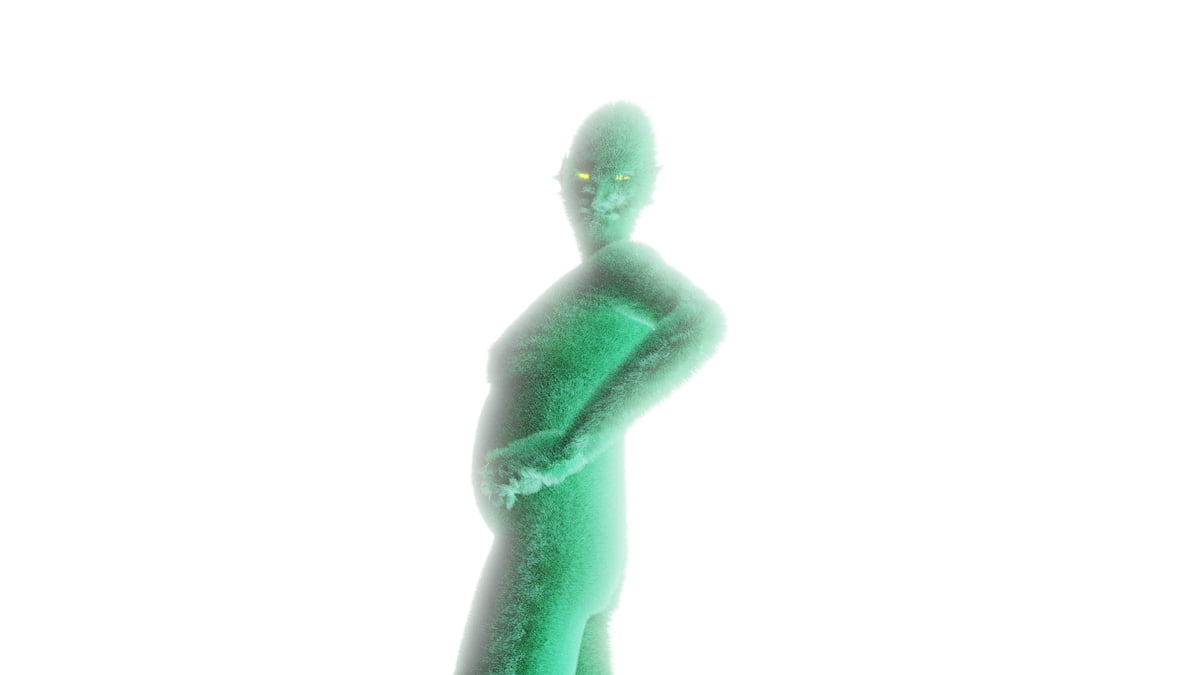

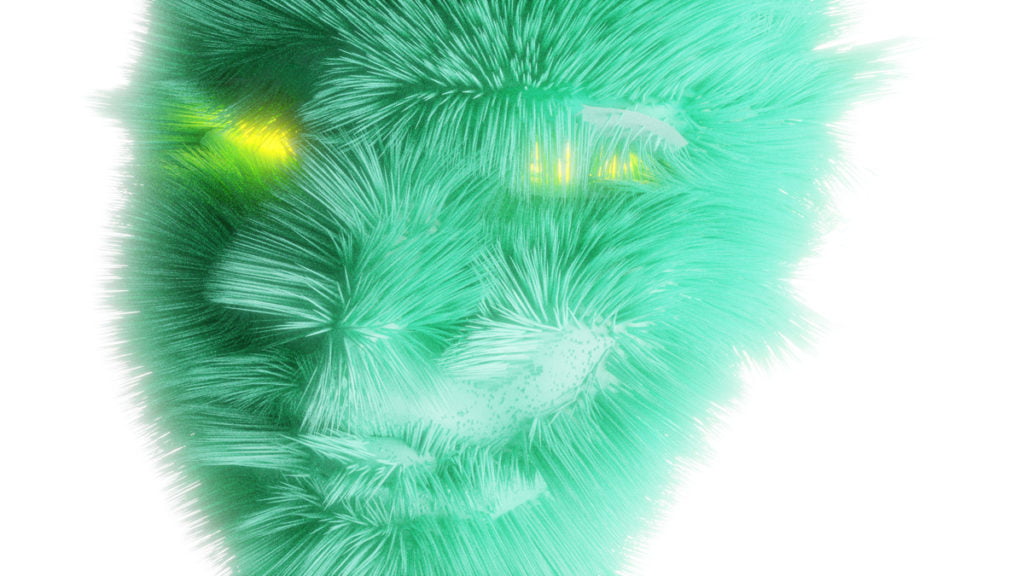

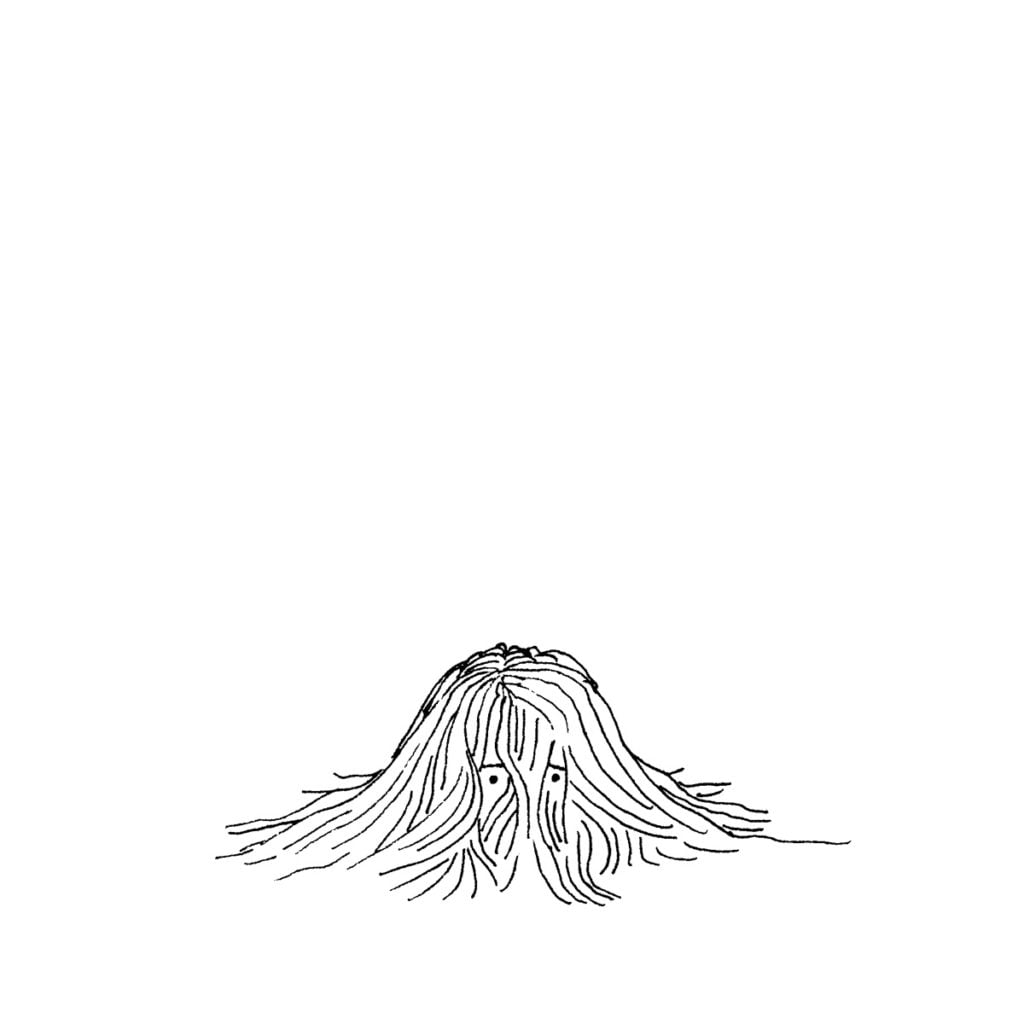

The window of this small room is wide open and the cold hits my body. I feel goosebumps on my back and arms. I knead my body for heat, cross my hands, close my eyes, throw my arms around myself and quickly massage my arms up and down. I’m startled as my fingertips move down to my forearms, I pull my fingers away and open my eyes. My forearm is covered in densely growing hairs, three to four centimetre long. The texture is like a gosling’s down, the soft and light hairs move in the wind that is coming in through the window.

Quickly reassured, I remind myself what is going on. This will take some time to get used to, the hairs are growing ever faster, and I can see considerable difference from one day to the next in how thick and long the hairs grow. I stand up from the bed and walk in front of the mirror by the bed.

I observe how the hairs seem to grow most quickly on my arms, legs, chest and back, but less around the genital area. I turn around and look over my shoulders, my buttocks are still hairless. I smile through a small moustache that any teenage boy could be proud of. My face is getting hairy, everywhere but around the eyes and the ears. I feel relatively self-content. This is all by the book, and according to what the doctor told me. Soon the body will adapt completely, and I will have beautiful hair growing all over my body. Thick, healthy hair.