This contribution presents a series of artistic practices that reflect different aspects of indigenous placemaking. Common among several indigenous cultures is a relationship to land based on principles of reciprocity, where giving and taking is a mutually beneficial practice. This challenges many Western cultures’ tendency to mainly consider land from a utilitarian perspective, prioritising extraction for shorter-term economic gains over more long-lasting values like connection, co-habitation and co-existence. Centring indigenous research, the aim of the panel was to examine the intricacies of placemaking based on principles of relationality and reciprocity. How can we re-think our relationship to land through the practices of art, design and architecture?

To respond to this question, artist and researcher Lisa Nyberg invited Sandi Hilal, a Palestinian architect, for her commitment to indigenous resilience and the displaced, and her question on how to host on hostile lands; Geir Tore Holm for his experience as a Sámi farmer, teacher and artist, to share how to create community through food and storytelling; Katarina Pirak Sikku, Sámi artist, to share her research on the horizon of grief, and her intentions to write herself into the landscape; and Marit-Shirin Carolasdotter, dancer and choreographer with Sámi and Kurdish heritage, because of her knowledge of the body and the land through her research project “Humans and Soil”. Nyberg hosted the panel as the firekeeper.

Convening on the Land

Lisa Nyberg

This contribution presents a series of artistic practices that reflect different aspects of indigenous placemaking. The participating artists were invited to the “Hurricanes and Scaffolding” symposium on Artistic Research 2024 in Ubmeje, Sápmi, to present their artistic research in an interdisciplinary panel focused on the challenges of placemaking on land impacted by settler colonialism.

Common among many indigenous cultures is a relationship to land based on principles of reciprocity, where giving and taking is a mutually beneficial practice.[1] This challenges dominant Western cultural tendencies to mainly consider land from a utilitarian perspective, prioritising extraction for shorter-term economic gains over more long-lasting values like connection, co-habitation and co-existence. Centring indigenous research, the aim of the panel was to examine the intricacies of placemaking based on principles of relationality and reciprocity, to re-think our relationship to land through the practices of art, design and architecture.

To explore these questions, I invited Sandi Hilal, a Palestinian architect, for her commitment to indigenous resilience and the displaced, and her questions about how to host on hostile lands. I invited Geir Tore Holm for his experience as a Sámi farmer, teacher and artist from Olmmáivággi/Manndalen, to show us how to create community through food and storytelling. I invited Katarina Pirak Sikku, Sámi artist from Jåhkåmåhkke, to share her research on the horizon of grief and her intentions to write herself into the landscape. I invited Marit-Shirin Carolasdotter, dancer and choreographer with Sámi and Kurdish heritage, because of her knowledge of the body and the land through her research project “Humans and Soil”.[2]

My contribution to the conference was as the firekeeper; I hosted the panel by keeping the fire going and brewing coffee to serve. Geir Tore Holm came from Norway with “space cookies” that told a story from the coast to inland and back. Marit-Shirin Carolasdotter offered us movement to re-member what has been dismembered. Sandi Hilal sent us a video proposal on how to demand and create repair while witnessing a genocide. And Katarina Pirak Sikku joined us online with a presentation of some of the maps, markings and artefacts from her archive.

The invited participants all have knowledge that expands well beyond the academic—of organising, community building, hosting space, sharing knowledge, making art, practising duodji[3]. They have knowledge of the body’s, the architecture’s, the food’s, the clothes’, the fire’s relationships to land. They have experience navigating violent governing structures and policy, of moving beyond borders and between worlds.

Our diverse research is practice based, and practice needs space and time to be shared. The structure of a classic panel—a stage where everyone gets 15 minutes to pitch their research followed by a conversation—did not seem appropriate for this theme. We needed to have time together and to be on the land. We hosted a space in the form of a lávvuo, a tentipi of Sámi origin, on the riverbank outside the university buildings, transgressing the limitations of a two-hour panel-session format as well as the campus architecture.[4]

The lávvuo offers a sense of place that is immediately connected to the land. Stepping out of the campus buildings and into the lávvuo demands a shift in attention—from the comfortable ignorance of our body’s vulnerability that the controlled indoor climate provides to the uncomfortable insight that we need to generate the shelter necessary to survive. It is an embodied experience—the land is right there—framed by the river’s steady flow, grass from last summer poking out through the snow, hard patches of treacherous ice, the smell and feel of the wind, the short hours with a pale sun to the long night under a dome of stars.

The lávvuo made apparent the panellists’ knowledge of what it means to be on the land. The conference was held in December, which had us prepare for many kinds of weather—snow or rain, wind or sun, hard ice from the fluctuating temperatures or a thick layer of soft snow. The lávvuo is made from canvas and has no floor. Keeping warm is of the essence. As the cold tends to rise through the feet, our student helpers, Sebastian Blind and My Maanmies, gathered branches of pine to put on the floor. Jon-Krista Jonsson, who lent his lávvuo to us, offered an abundance of reindeer skin to sit on, but also to put at our feet. As there was too little snow to cover the gaps in the canvas, we supplemented the fire with heating fans to warm up the space in the morning, then trusted that our bodies would generate heat throughout the day.

Hosting the space demanded more work from us all, but it also allowed us to set the parameters for how others could engage with our art and research. An invitation to the visitors was written in a pamphlet that accompanied the conference programme: “When you enter this space, you bring your places of belonging with you.” We wanted to remind visitors of the places they belong to and how these impact how we move in the world. Many, if not most of us, have experience of unwillingly leaving places behind that we still feel we belong to, or try to reconnect with. Sometimes it is impossible to return, sometimes the place is gone. Still, the principle of reciprocity offers some solace that the places we belong to might miss us too, and this relationship connects us.[5]

When visitors entered the space, they were met by a closed zip at the entrance of the lávvuo. Some went directly for the zip, others waited patiently to be invited, a few knew the Sámi custom of announcing one’s presence before entering. To step in you need to bow your head and dive in, immediately finding yourself very visibly part of the outer circle. This became its own choreography—coming in, looking around, being acknowledged by the people present, and someone making the welcoming gesture by scooting along to offer seating on the bench. Participants and visitors alike generously took turns inviting people in.

My hope was to provide a space for us to show, rather than tell, what research based on indigenous principles of land relations and reciprocity can look like, without losing sight of the impossibility of fully manifesting this under imposed academic structures. At an academic conference, time is limited and so is participants’ attention spans. Intense programming favours clear, easily communicated projects that are smoothly transferable, but epistemic ignorance is about more than time. As much as we try to re-think knowledge beyond the hegemonic, it is challenging to translate the nuanced, collective and time-consuming practices of indigenous research into easy digestible formats. What if we refuse? What if we take seriously our efforts to think of knowledge as circular, or emergent? And, in the words of Kuokkanen, what if we counteract epistemic ignorance by drawing “everyone in the academy into the process of creating new knowledge”?[6]

We were acutely aware of the risks involved in trying to share indigenous knowledge and aesthetics in an academic setting. There is the risk of exotification, of othering and being the mirror that defines the hegemony. There is the risk of appropriation, of appealing to the university marketing team, acting as an aesthetic manifestation of their multicultural accomplishments. There are the risks of indigenous knowledge to be seen as historical, rather than as part of contemporary thought, and expecting “correct” representation of Sámi practices and Palestinian customs, stemming from the idea of indigenous knowledges as traditionally pure.

The lávvuo was an imperfect experience, placed in the tension between where we are and where we want to be. All the risks we feared did to some extent manifest themselves, seeping into questions and conversations, but they did not dominate. The lávvuo did not offer refuge, but was an opening to have uncomfortable conversations, such as how to be artists and researchers in times of genocide, the risk of appropriation of indigenous knowledge when entering academia, or how to host on settler-colonial land. It also functioned as confirmation of the importance of reciprocal ways of sharing knowledge, ways that are more prevalent outside of a European academic context, as confirmed by visitors arriving in Ubmeje from other continents.

In this visual essay, you can find documentation of our day in the lávvuo in the form of texts, pictures, paintings, an interview and a recipe. We chose to prioritise our time together over intrusive documentation practices (video, sound, etc.), trusting that the dissemination of our research will take place mainly through the people who participated. Aimed at other artists as well as researchers, the documentation is heavier on the practice side than the analysis. Or maybe we just need more time to fully understand what our efforts made possible.

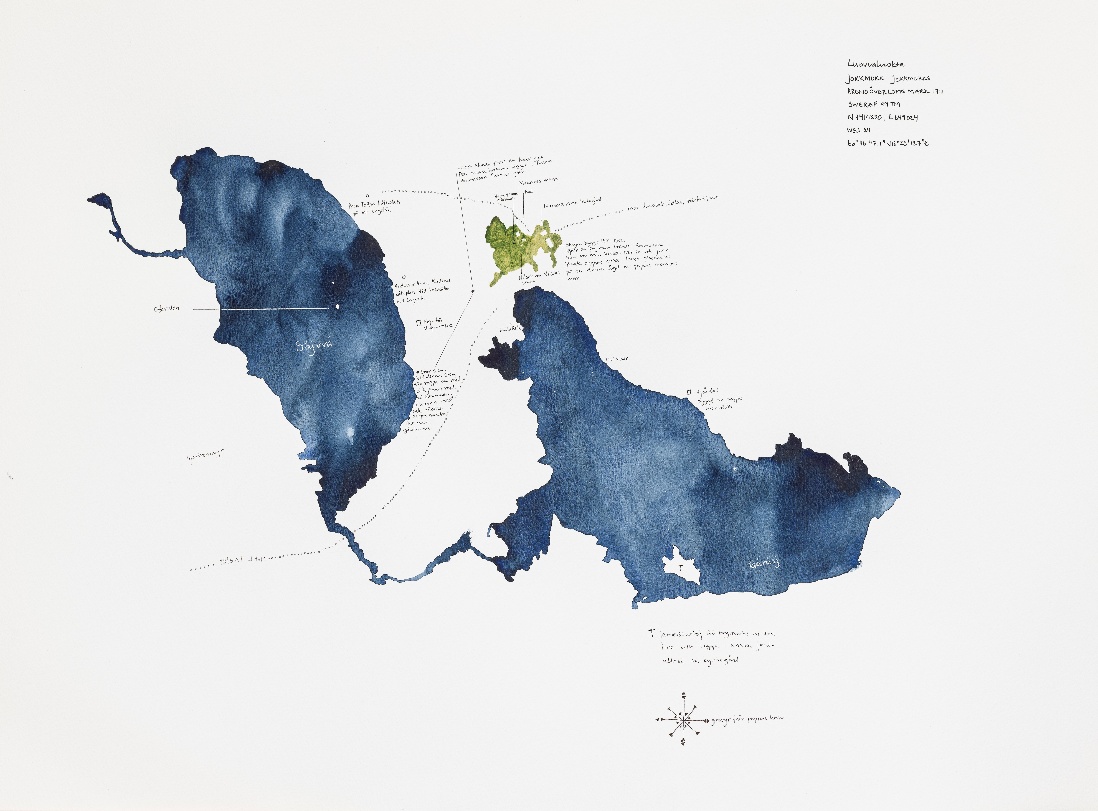

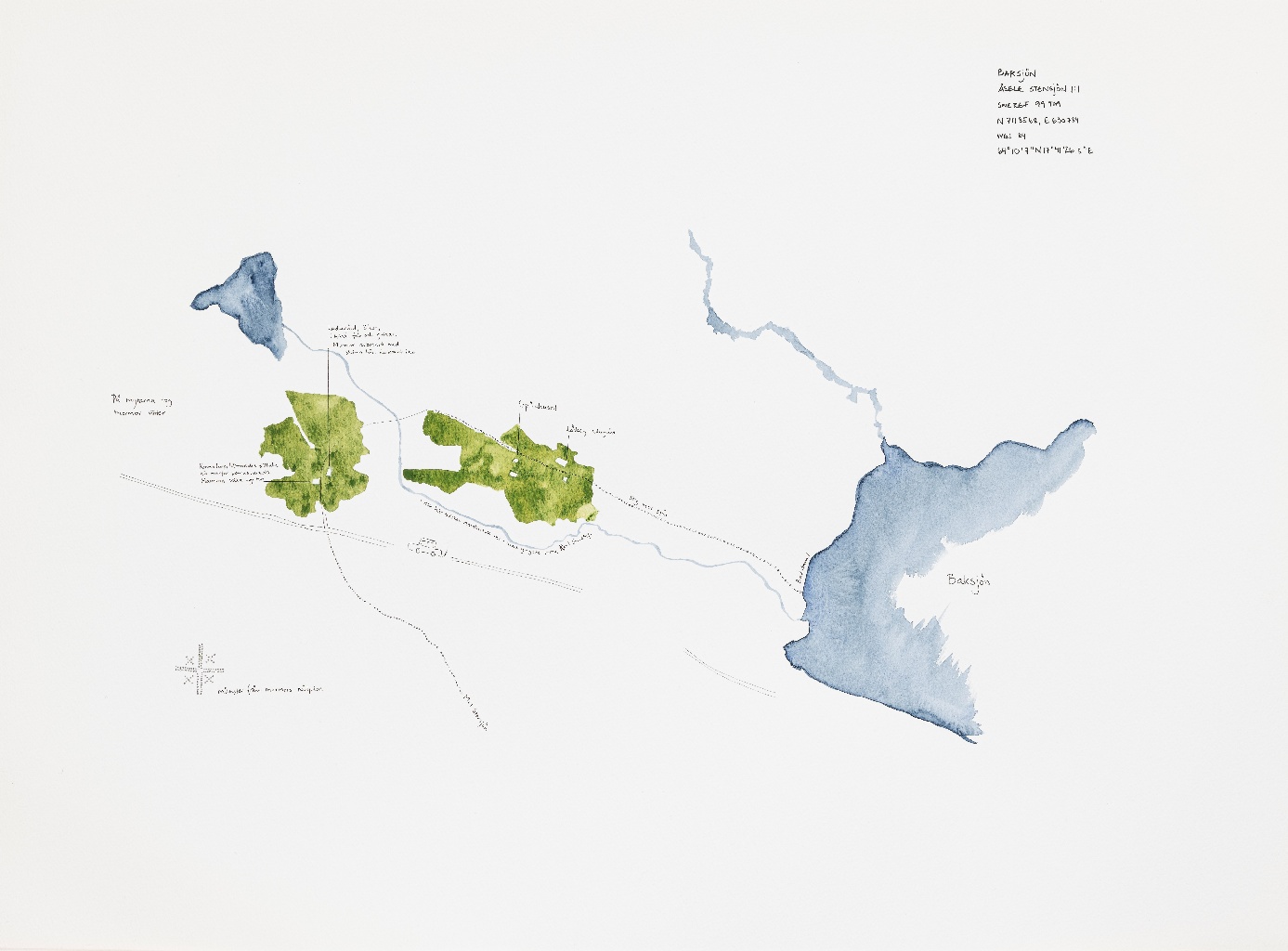

Katarina Pirak Sikku vuorkkás / From Katarina Pirak Sikku’s Archive:

Birága ja Klementssone johtolagat / Piraks och Klementsson’s trails

Katarina Pirak Sikku

Katarina Pirak Sikku builds her own archive. Fills it with history from her own background. The oral stories she has heard as a child she fills with findings she has made in the state archives she has visited in recent years. She has drawn maps of her family’s lands, the ones they own and travel through. Ownership is not a legal property but a spiritual property. The map marks cemeteries and landmarks that all carry a history, known to some, unknown to most. Growing up, Katarina Pirak Sikku got to know these places but also heard about places that were never allowed to be visited. These were sacred and significant places whose geographical locations were kept secret to protect them. If they were revealed, they would most certainly be visited by an ethnologist who would dig them up and take everything of value to the museum. The better the protection, the less the places were mentioned, the more the place fell into oblivion. Also among those who had the task of guarding them.[7]

We, the Sami people, have demanded an apology from the Swedish state, a reconciliation process, repatriation, and the return of Sami cultural objects and human remains. We are met by a recalcitrant state. Do we need apologies, reconciliations and repatriations? Can we become mentally independent? What I mean is that I want to become a subject in history, to shape my own self-image and have the power to define myself. I believe that mental independence is not a state, it is an ongoing process, a doing, a constant trying. I want to free myself from the limiting mechanisms of unfreedom in order to be able to freely face, illuminate, narrate and analyse the issues. I want to find an artistic entry into my research to be able to portray the sadness that I experience as a Sami as a consequence of colonialisation, assimilation policies and the theft of Sami lands. I want to use art’s ability to raise issues through a constant pushing of boundaries, its ability to portray that which is difficult to understand rationally, and try to dissolve the petrified losses that are impossible to put into words. I want to reclaim the power to define myself, to recall my name, my place and to inscribe myself in the landscape.

Space Cookies: Taking You from Coast to Inland and Back Again

Geir Tore Holm

These cookies are not traditional but mark connections between people and their landscapes in Sápmi since time immemorial. The coastal areas, with their abundance of edibles, materials and possibilities of seaway transportation are related to the rich forests, mountains and tundra by nomadism, migration and kinship. Think about how what we put in our mouths provides nourishment to longing, belonging and even conflicts about land and more. How does space taste?

Keeping Time Through Rhythm

Lisa Nyberg

It takes patience to awaken the fire and to keep it alive. There are preparations involved. Collecting the dried wood and the birch bark, or finding raw wood and smaller sticks and twigs on site. Bringing matches and an axe or a knife. Finding the right stones for árnnie—the fireplace. The stones should be round and neither too small nor too large. They are best found in streams.

You can protect the fireplace from the wind with your body. Light the match. Keep the fragile flame in the middle of your cupped hand. Don’t rush. Pass it on to the folded birch bark strip, on to more strips and add it to the kindling. Let the fire take hold. Do not rush it with large pieces of wood. Blow lightly in the right place. Then forcefully. The fire starts to roar. You can add more wood now.

There is a soft rhythm, a warm focus and attentiveness to keeping a fire. Caring for the flames to stay clear, for the heat to burn off the ashes so as not to create too much smoke. Keeping the logs close enough to preserve the heat while making sure oxygen can pass through and feed the flames. Watching how the intensity of the glow shifts and how the colours change.

The fire has many sounds. Exciting and dangerous crackling. Hissing and howling. Painful whining and joyful singing. A short whistle to announce that someone is coming, and we answer, “yes come, we’re home.”[8] The ash rises towards that sky and falls softly around us. The stillness of the glow in stable heat.

To make the coffee, I follow the teachings of my grandfather. He is long gone, but I borrowed his pot and his coffee box made from birch bark from my father. I start with filling the pot two thirds of the way with fresh water and put it on the fire until it almost boils. Then I pour the ground coffee on top in the shape of a mountain. I put the pot close to the fire, watching as the ground sinks and waiting for the water to heat up, but not to boil. This means moving the pot back and forth from the heat a few times to give it time to make a proper brew. I have a special stick to hold the pot that my father just made for me, en måg, an old Swedish word that translates as son-in-law.

When I sense that the coffee is done, I move it away from the fire onto a stone where it can rest and clear. I put the lid on the pot and pour some water through the pipe to rinse it from ground. While I wait, I rearrange the fire and add more wood. This lights up the room and I get a break from tending to the pot to acknowledge the people around me. A spark of energy moves across the room. People take the opportunity to stir, to shift in their seats, to acknowledge their bodies’ need for movement. They see and adapt to each other, speak a little louder or let out a laugh to release some tension, before they settle down in new positions.

It is time to serve the coffee. The first drops I offer to the land by pouring it directly on the ground. Then I fill the cups and pass them round. Some people have brought their own cups, or gukssie, kåsa in Swedish, with their individual design and beauty. I can only reach the people closest to me, so everyone helps out by passing the cups along. I look for the people in the back to make sure they get a taste, and I see their smiles and faces. When the ground starts to show at the bottom of the pot, I move to båssjuo, the kitchen, to empty and clean it before I fill it up again. By this time the fire has calmed down and I find a good spot for the pot.

The rhythm of making and serving the coffee, while keeping the fire, creates a circular sense of time. The ongoing conversation renews itself with regular intervals, as we fill and refill our cups. People switch places in the lávvuo as new people enter and others leave. The conversation gains new oxygen with the air coming in from outside, with every new person, with every piece of wood put on the fire. The conversations calm down as the fire settles and the room gets darker and more still. The students ask the room about knowledge and the answers come from everywhere. Åsa tells us about what to do when you hear a crying baby on the mountain. Sebastian shares his gratitude for being invited to a lávvuo for the very first time. Someone simply cries and is comforted.

The day begins its end when I put the last piece of wood on the fire. As the fire turns to ash, darkness falls and the big conversation splits into many small ones. We prepare to leave but there is no rush, the fire goes out slowly. We work together in the dark, cleaning up after ourselves and returning the land to its original state. We thank each other for the space we have offered one another and hope to meet again soon.

…

This text is a documentation of the role of the firekeeper. This way of hosting came out of a strong need to centre fire-keeping as a practice that carries knowledge and epistemologies across generations. I wanted a fireside conversation that was not metaphorical, but actual—the fire being a living entity and actor within it. A space to sit with me by the fire, to talk to the fire and me, to talk to the fire and each other through the formation of a circle with a focused centre.

It became apparent that this space favoured listening. The magnetic light, sound and movement of the fire formed a place to rest one’s eyes, one’s ears, one’s mind, while focusing on the speaking voice. There were no empty silences to fill and less of a feeling of urgency for someone to respond. The conversation slowed down and there were slight shifts in direction, from speaking back and forth to statements that together filled the space between us.

Sitting closely side by side, sharing something to eat, passing cups along, creates a learning space with specific qualities. For me, it resembles the space of risk that I aim for in my teaching, where we hold each other through difficult conversations and radical study that change our thinking at the roots—a space that favours pedagogies of the unknown, that can hold the contradiction of learning for the future by focusing, intently, on the present.[9]

Proposal While Witnessing a Genocide

Sandi Hilal

How can we create life?

In her video, Proposal while witnessing a genocide (2024), Sandi Hilal shares her experience of being an architect, an artist and a woman who is part of the larger community of people who are seeing the genocide in Gaza play out in front of their eyes. Her response is to give us the task of how to create life among all this death; what can we do, how do we act, in times of genocide? Hilal offers us the possibility of demanding and creating repair from the positions of power that we inhabit.

The video was filmed in the performative artwork Al-Madhafah (the Livingroom), as part of “My New Museum?”, an experimental platform for investigating the future of museums by Malmö Art Museum. It was first screened at Malmö Konsthall on 10 March 2024.[10]

Dismemberment and Remembering

An interview with Marit-Shirin Carolasdotter by Lisa Nyberg

Lisa Nyberg (LN): What is your definition of reciprocity and how does it play out in your practice?

Marit-Shirin Carolasdotter (M-SC): Reciprocity, in my work, in my practice, is related to my indigeneity. It starts with stories and the way of sharing stories. It is a way of creating relationality. I like how Linda Tuhiwai Smith talks about gathering witnesses, or testimonies—in what sense do we listen to testimonies?[11]

The indigenous way of reciprocity is to think about how we receive testimonies, how we listen to them in a decolonial way, and how to give back. I also come to think about something that scholar Aminata Cairo talks about.[12] She emphasises that we need to consider who is entitled to hear and carry my story. Are you entitled to my story? What do we share and how are we heard? We can discuss a lot of things, like ownership or agency, but I think that those questions are some building blocks that I am to think of when it comes to reciprocity.

LN: When you talk about the “we”—who do you refer to?

M-SC: When I’m talking about “we”, I think of us as human beings or human persons, or “we” as carriers of collective stories. I think that goes for everyone, no matter what the cultural identification of a person is. In this sense I’m talking about “we” in a sort of broad definition. I see my own position as belonging to several cultures and communities. Then again, reciprocity is not only related to human beings but also to non-human beings and bodies; we can start to move more into how to pass down knowledge of indigenous peoples, about giving the story and receiving the story.

LN: I hear the gift as being part of this conversation too, about giving and receiving stories?

M-SC: I cannot speak from how it is specifically in Sámi culture, but if I speak from my Kurdish heritage, the idea of the gift can also be an idea of storytelling and sharing as a medicine. Artistically, we can create something that will help another to become aware, to recover from something. We pass knowledge down or on, thinking about generations to come. If we start to refer to specific principles of reciprocity from different indigenous cultures, different languages start to come together.

LN: Do you want to say something about this idea of dismemberment and remembering, and the role of the body?

M-SC: Since about 2019, I have been busy with creating an artistic practice based on interviews with global indigenous artists and by including my own body and its close relationship to the soil or the ground. Indigenous peoples are fighting for repatriation of bodies and human remains that have been excavated and exploited by colonial powers. I was invited by the Ainu women’s association in Sapporo, Hokkaido, and Professor Hiroshi Maruyama to visit them. What I found was that when human remains were dismembered and separated from each other, the Ainu people considered those bodies to be unable to move on to the next world as full persons.

Dismemberment is disrupting not only the right to after-death personhood, but also to their generational and spiritual knowledge. If personhood is lost, so are their stories, that is to say, when we are listening to the testimonies of indigenous stories, it helps us remember the histories of collectiveness—when putting together the bones again, we remember who we were, who our ancestors were. Coloniality has disrupted and dismembered these testimonies by, for example, the excavation of human bodies for the benefit of experimental studies.

So, remembering for me is an attempt to reconnect with the Earth and with the body. Remembering the ancestors, remembering the knowledge, remembering the land. I started to think about the dismembering of the world and dismembering of nature through exploitation and extraction. So, we have this work to do: to start to remember. To remember everything, to put it together again, to make a person, a spirit, a body. To create those relations again.

LN: How does this translate into movement?

M-SC: I developed a meditative practice, or a reflective practice, a very slow one, in which movement is happening and something is reconnected. I haven’t researched the following yet, but it would be interesting to see what happens to our different neural patterns and to see what is somatically going on in the body while we’re doing that kind of practice. So, in movement I created this process where I started to work somatically with the bones to see what happens to my relationship to them, remembering dismemberment from ancestors and land, imagining them being separated and stacked in piles, like those non-repatriated bones. The idea was first to imagine, or attempt to sense, how my body would be if it was dismembered. How would I move? Could I move at all? If I imagine that I can move because I’m part of the soil, I’m part of the life that is in there and I’m part of decomposition or being grown into something else together with that soil, then maybe I could start to act, act as if I were dismembering my body too, and then move into the memory—memory of that body, memory of that place, memory of that soil.

LN: Is there a connection between this practice and the movement you led us through in the lávvuo?

M-SC: Maybe I wasn’t aware of it while I offered the proposition, but I noticed how there is something about the hands and seeing a bunch of arms in the air. The pattern you see is similar to that in prehistoric cave art, to how people started to leave their traces that say, we are here. I see these hands as patterns. For me, the main thing was that there was a ritual going on here that was maybe a bit older than we think it was.

LN: I think so too. I don’t know why the word “simple” comes up, because that could translate as very close to the heart, or very recognisable or common. But the great thing with something common is that everyone can do it. It’s a small gesture, but as a group it’s a big gesture! We seldom put our hands above our head and shoulders in civilised society. As a group you are suddenly in this collective thing and you move, the air moves around, and you can smell each other’s armpits and create an energy shift in the space, right?

M-SC: The lávvuo was a very special and concentrated space, which is super great, but something happens when we try too hard to hold it. It is common, in both artistic and academic settings, that people are in a state of receiving and trying to hold what comes at them. It comes at you from the front and is held somewhere in the body. But what if, instead of attempting to contain whatever is coming at you, you let go and you give up that energy? We did some sounds together in the lávvuo, through ululating—this Kurdish ti-li-li-li-li!—to let our voices out, releasing tension and really singing with the spirit. The fire was going up, the smoke was going up, so we had to go with it.

LN: Could you tell me about the participatory performance we did on the second day, called Leaveno Trace, and how it is related to your idea of “decolonial ritual”? We formed a circle and jumped together, you led us in the joik “We speak Earth” by Sara Marielle Gaup Beaska, and we cleaned up the space and found places to return the pine branches to the land.

M-SC: To come together on a simple task of cleaning the space, or even forming a circle, there’s already something there about decolonial practice. Because ritual can be many, many things. Ritual can be acting on something or evoking something, but ritual could also be repeating everyday tasks. So, “leave no trace” is part of indigenous practices, to make sure that we are not disrupting the soil of where we have been. There is a care in that for sure. There’s a spirituality behind it, and it’s also a practical thing. All this goes together, it is in our compass.

The proposition of movement following our gatherings in the lávvuo was to remember our collectiveness and honour it by working on the now where the lávvuo was placed, establishing a sense of what the indigenous phrase “leave no trace” might mean in practical use.

I also wanted to try to relate the performance to the place where we were. Do we actually recognise that this lávvuo may have been standing here for a very, very long time? Can we imagine that? This lávvuo was not only a space where we were and then suddenly it was not there. There’s always traces of our conversations, and we are not trying to wipe them away, but we are having a ritual to recognise what happened here. The ritual was part of beginning something that had already started before our time. We are not finishing but we are closing the circle somehow.

LN: I had that feeling when we did it; that we caught something, not to close it down or to end it, but just caught it so we could move on somehow.

M-SC: I have noticed that it’s really difficult for some people to sense a connection with a place or with the Earth. They may say that “I can’t feel it because all I can feel and see is concrete”, which I totally get. That is why I work with these principles, because something shifts in people’s bodies when they attempt to connect with the Earth. I have managed to do rooting practices or meditations, and I have been dancing a lot outside and standing with my feet on the ground. It is not concrete, but it’s concrete, it is the ground, I feel it. We are standing on the mountain, all of us. Taking that memory into another space makes it so it doesn’t really matter where we are. You know the ground is there. So yeah, I find it quite interesting that these times disconnect us so much we can hardly imagine that there is Earth down there. Decolonising practice could be that I refused to accept the concrete because I know—I know that the Earth is there.

Leave No Trace

Score by Marit-Shirin Carolasdotter

Await the people joining with curiosity

The expectations are allowed to be there, no matter if it is with estrangement or excitement

It will be cold outside, together with tired minds from the week

Receiving stories and testimonies of many, they will linger for many days ahead

But right now, we stand here, shaking together to get warm and meet each other’s eyes

Our task is to have a look at the snow.

Can you see the outline of a lávvuo that once stood here?

Can you sing in a way that speaks to the earth beneath the snow?

Our task is to make it seem like we were never here, but Mother Earth still remembers

It will be our way of honouring her, let us put back the twigs and spruce rice

Put it somewhere close to a tree

And let it breathe together again

Let us reconnect with the materials and memories of our conversations

With joy and understanding

Although a simple task, gratefulness is powerful

Leave no trace, but leave nothing behind

Footnotes

- Kuokkanen, Rauna. Reshaping the University: Responsibility, Indigenous Epistemes, and the Logic of the Gift. Vancouver: UBC press. 2008.↑

- More information about all participants can be found in the bios. ↑

- “Duodji is a customary practice of creation, involving aesthetics, knowledge(s) of materials, place and season, as well as a Sámi holistic worldview that touches upon spirituality, ethics and the interrelational qualities imbedded in the multiple world(s) of creation.” Finbog, Liisa-Rávná. It Speaks to You—making kin of people, duodji and stories in Sámi museums. New York: DIO Press. 2023. p. 15. ↑

- Lávvuo or låvdagåhtie. We have chosen to use Umesamiska, the local Sámi language, for naming specific Sámi objects or concepts. A special thanks to the organisation Álgguogåhtie for teaching us. ↑

- Lopez, Barry. Embrace Fearlessly the Burning World. Mirefoot: Notting Hill Editions. 2023. pp. 65-72. ↑

- Kuokkanen, Reshaping the University, p. 5. ↑

- Anders Jansson and Katarina Pirak Sikku for the exhibition “Ner till norr”, Bildmuseet, 2024 ↑

- Ryd, Yngve. Eld: Flammor och glöd—samisk eldkonst. Stockholm: Natur & Kultur. 2005. ↑

- Nyberg, Lisa. Pedagogies of the Unknown—studying for a future without guarantees. Stockholm: Books on Demand. 2022. ↑

- Al-Madhafah is a living room dedicated to hospitality, situated on the border between the private and the public sphere. The living room has the potential to question the roles of guest and host and give hospitality a different socio-political meaning. In Arab culture, hospitality is traditionally seen as a temporary practice. This belief is reflected in the Hadith, which states that hospitality prevails for three days, after which it becomes an act of charity. Al-Madhafah functions as both an architectural and political concept that challenges the narrow boundaries of public and private, guest and host, inclusion and exclusion, and advocates for the right of those who temporarily reside in a place to take on the role of hosts rather than eternal guests. ↑

- Tuhiwai Smith, Linda. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. 2021. ↑

- Aminata Cairo is a speaker, scholar, storyteller and “love-worker”. She is former Reader of Inclusive Education at The Hague University of Applied Sciences and former Reader of Social Justice and Diversity in the Arts at the Amsterdam University of the Arts. ↑