This article studies a set of works by Chinese-born French artist Shen Yuan presented in her solo exhibition—titled “Angling” (2 November 2022–9 July 2023)—at the Red Brick Art Museum in Beijing. Modelled on familiar household or personal items, Shen’s works materialise intimate life scenes “at home” while evoking multiple situations of displacement linked to transnational travel and migration, and, more recently, Covid-19 lockdowns. This article investigates how the specific material configuration of Shen’s works heightens people’s awareness of the affective agencies of quotidian things to cultivate affinities and alliances that are often neglected in the human-centred construction of identity, home and belonging. Moreover, it considers how Shen’s practice sheds light on the productive relational dimension of displacement, which makes it possible to unsettle and rework systems, orders and power relations that underpin the persistent hegemony of the Global North in the production of knowledge and discourses about nations, cultures, histories and otherness.

This article investigates a set of works by Chinese-born French artist Shen Yuan presented in her solo exhibition—titled “Angling” (2 November 2022-9 July 2023)—at the Red Brick Art Museum in Beijing. Modelled on familiar household or personal items, such as a tilt and turn window, a comb, a pillow and a set of bedsprings, Shen’s works materialise intimate life scenes “at home” while evoking multiple situations of displacement in association with transnational travel and migration, and, more recently, Covid-19 lockdowns. In Shen’s practice, home is never a place where people feel settled, safe and at ease. Rather, with her works, Shen engages herself and viewers in an endlessly drifting journey, whether physical or conceptual, to angle for encounters and connections with/in their immediate surroundings of inhabitation despite uncertainty and potential disturbance.

Shen (1959–) was born and brought up in Xianyou, a county in eastern Fujian province in China. She studied traditional Chinese painting at the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts, the predecessor of the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou. However, soon after her graduation in 1982, Shen turned to installation and sculptural works. In 1989, she was one of the very few women artists whose works appeared in the groundbreaking exhibition “China/Avant-Garde” (5–19 February) held at the National Art Museum of China in Beijing. One year later, she moved to France to join her husband, the artist Huang Yongping, who decided to stay in Paris after participating in “Magiciens de la Terre” (18 May–14 August 1989) at the Centre Georges Pompidou—one of the first exhibitions that featured global contemporary art. In response to her experience of transnational migration and resettlement, situations of home and displacement have been repeatedly explored in Shen’s practice since the early 1990s.

One of the works conceived and created during the first few years after her move to Paris is Wasting One’s Spittle (1994). Made from a mixture of drinkable liquids, including water, Coca Cola, red wine and orange juice, nine large ice tongues were attached to the walls and pillars of a narrow basement in Paris which was used as a temporary exhibition site. Under each ice tongue was a copper spittoon. Over time, the tongues started to soften and melt. Drop by drop, the melting tongues dripped into the metal spittoons, producing intermittent sounds of drip-drop, while creating various shapes and forms. The work brought to the fore a lively scene of diversity and multiplicity, which could hardly conform to any homogenising practices of assimilation that tend to negate or suppress difference and alterity caused by transnational migration. Gradually, it was revealed that each ice tongue was supported by a sharp and pointed kitchen knife nailed to the wall. The sound vanished at the end, and viewers were exposed to the silent truth of cruelty.

Shen did not speak any French when she first landed in Paris. With her work, Shen activated viewers’ multisensory involvements with the affective becoming of an embodied form of otherness beyond language barriers, communicating her otherwise inarticulate experience of helplessness and displacement as a newly arrived immigrant inhabiting a foreign environment.[1] Made of easily accessible items in her everyday surroundings, Shen’s work demonstrates a mode of homemaking in displacement that cultivates generative caring relations across things and people, despite palpable conditions of disquiet and disturbance. This is also evident in Shen’s practice after she had settled in Paris while travelling widely across the world for exhibitions, biennales, art fairs and artists’ residencies.

In this article, the investigation of displacement is related but not limited to the typical situations of transnational migration and relocation. Most of the works presented in “Angling” were completed between 2020 and 2021 amid the raging pandemic, when the artist was forced to stay at home and displaced from a “proper” social life. Moreover, shortly before the global outbreak of Covid-19, the artist’s husband passed away, which made her feel even more isolated and distressed when encountering enforced authoritative measures of social distancing during the pandemic. At the time, it was with her works of art that Shen created an important means of communication which enabled her to rekindle and remake her social connections beyond the confines of the private home.

Here I consider how Shen, through her creative engagements with mundane household or personal items, explores and demonstrates the affective material capacity of art to engender experiences of interdependence and relatedness on a bodily sensuous level across geographical, cultural and linguistic differences. While unsettling the notion of home in association with comfort and reassurance, the discussion investigates how Shen’s practice provides distinctive insights into the relational dimension of displacement marked by not just rupture and disjunction, but also generative affinities and crossings, which make it possible to reconfigure and rework both boundaries and mutualities between self and other, private and public, past and present as well as home and abroad in an iterative and open-ended manner.

Displacement: Forging Caring Relations

As suggested, Shen’s practice often takes inspirations from her everyday life environment, cultivating caring relations with seemingly trivial and unremarkable household materials and objects, which are, however, deliberately configured or altered to create various situations of displacement. Recalling intimate scenes of mundane domesticity while evoking dislocation and unease, with her work Shen intensifies the embodied engagement of viewers who actively take part in her artistic exploration of home. Through her practice, Shen sheds light on “the paradoxically productive” and “profoundly relational qualities of displacement”, in stark contrast to the widespread use of the term within the global humanitarian framework since the end of World War II, especially pertinent to forced migration and refugeehood that require institutional interventions on the national and international levels for (re)settlement, integration or repatriation.[2]

Based on her years of studies into the turbulent living conditions in southern Africa—Zimbabwe in particular—Amanda Hammar proposes a relational approach to displacement.[3] She suggests to enrich and complicate the solution-driven humanitarian configuration of displacement, which, in spite of “its best intentions to protect and care”, ultimately reinforces the existing political and administrative regimes that naturalise the reduced representation of the displaced in relation to victimhood and passivity.[4] Hammar’s discussion, in general, still centres around forced movement and displacement. Nonetheless, it brings attention to “concrete and differentiated losses and gains” experienced by displaced individuals or communities whose engagements with migration and resettlement make contributions to the continuous, but subtle (re)formation of socio-economic and political systems and orders within and beyond specific national contexts.[5] Meanwhile, for Hammar, it is important to take into consideration a range of actors and forces unevenly affected by and effecting conditions, relations and lived experiences that are producing and produced through displacement.[6] According to her, this relational approach to displacement is “applicable well beyond the specific ‘case’ of Zimbabwe and southern Africa”, and could also be extended to the studies of people’s lives within diverse ever-changing environments.[7]

Indeed, Shen’s migration from China to France for better professional development, and her later involvement in frequent cross-border movements and exchanges that characterise the ever-more globalised contemporary art world are a far cry from the turbulent cases of forced displacement examined by Hammar. This article does not, by any means, tend to obscure the remarkable distinction between the two. In my discussion, Hammar’s relational model of displacement is adopted as a methodological approach to analysing Shen’s works, which materialise tangible situations of inhabitation linked to transnational migration, the Covid-19 crisis and the experience of bereavement. As indicated with Wasting One’s Spittle, displacement is less about enforced physical dislocation and more about turning points to forge materially grounded and bodily affected relations that traverse clear-cut boundaries between self and other, local and foreign, as well as personal and social. Through interrelated practices of making and perceiving art, the artist, embodied viewers and quotidian domestic items are engaged with for the co-production of multiple conditions of home in displacement.

Shen’s careful and creative engagements with mundane household or personal items might be reminiscent of, but not necessarily limited to, women’s lived experiences at home. As she suggests, by making works that “come from their daily experience, their authentic understandings of life. There is tear and blood. Feelings come from life, truly experienced life, be it political, social or private.”[8] With her work, Shen brings to the fore the significance of quotidian homemaking practices, which enable people, especially those who have been involved in various forms of displacement, to forge mutually constitutive caring relations with/in their immediate surroundings of daily inhabitation without negating disparities and discords. Care, here, has nothing to do with a moral disposition concerning the appropriate ways of accommodating cases of displacement. Rather, with a specific focus on the affective material dimension of Shen’s practice, in what follows I draw upon María Puig de la Bellacasa’s more-than-human configuration of care.[9]

Far from perpetuating “normative moral obligation”, Puig de la Bellacasa investigates the relational and material nature of care that cultivates affinities and alliances, making it possible to disrupt and displace categorical divisions and hierarchies imposed on interdependent human and nonhuman actors.[10] Furthermore, according to her, the construction of caring relations does not necessarily smooth over divergences, discords or forces of exclusion and oppression.[11] In contrast, it is what are currently not included in the flourishing of heterogeneous and interdependent forms of matter and life that hold potentials to stretch and expand people’s habitual perceptions and understandings of the world they actively inhabit and take part in its constant relational remaking.[12] In the following sections, I will discuss and unpack how Shen implicates herself and viewers in various carefully materialised conditions that produce and are produced through displacement, giving rise to perpetually open contestations and constructions of home, relatedness, belonging and otherness.

Pêcher l’air de Paris

Pêcher l’air de Paris (2020) is the first piece that comes into view after entering the exhibition “Angling”. The main part of the work is a full-length wooden-framed French window. It could be either completely opened without a central mullion or only partially unhinged from the top like a typical tilt and turn window (Fig. 1).

The artist found this dual-purpose French window at a flea market in Paris. She then painted its frames turquoise to resemble Marcel Duchamp’s 1920 readymade sculpture Fresh Widow. The title of Duchamp’s work plays with a double entendre based on the visual similarity between “French window” and “fresh widow”. With all the window panes covered by black leather, it denies both light and airflow, evoking an enclosed, suffocating interior space.[13] Produced shortly after the end of World War I, the piece, in a way, alludes to the cruelty of war, which resulted in a considerable number of women as recent widows wearing black in mourning.[14] By referring to Duchamp’s work, Shen acknowledges her own identity as a fresh widow when conceiving and producing Pêcher l’air de Paris.

To ensure a good balance when placed on the ground, the French window in the exhibition is attached to a piece of steel plate. One set of the windows is tilted inwards, leaving a narrow gap. A dried bamboo cane, taken from the artist’s open balcony at home where she grows some plants and flowers, is inserted through the window opening. Looking at the work from the side, the protruding bamboo cane appears like a fishing pole angling for connections beyond the confined interiority of the private home. This reveals some original ideas about the exhibition, titled “Angling”. Experiencing the pain of grief at a time of a global pandemic when everyday activities were highly restricted, through her practice Shen intended to reconnect herself with the wider external world.

Hung from the bamboo cane by strings knotted with disposable surgical masks is an empty glass vessel. It calls to mind another readymade by Duchamp—Air de Paris (50 cc of Paris Air)—closely related to the artist’s transcontinental itineraries. The original piece was created in 1919. Shortly before heading back to America, Duchamp visited a local pharmacy in Paris and bought an empty glass phial that contained no content but fresh Paris air as a souvenir for his friend and patron Walter C. Arensberg. Despite its transparent and inodorous quality, air could be the most genuine and vibrant element of Paris life. By including another empty glass container as part of her installation work, Shen communicates her longing not only for fresh air over the course of large-scale lockdowns, but also for the return of a normal, properly functioning world, in which people can travel and work within and across different countries and regions without additional restrictions.

According to Hammar, displacement is not seen as “a singular or discrete phenomenon, but rather as part of a more complex, layered continuum of inclusions and exclusions, of possibilities and impossibilities.”[15] In addition to her earlier works, such as Wasting One’s Spittle, closely linked to her inhabitation of an unfamiliar foreign environment, Shen’s recent practice extends and complicates her exploration of homemaking by attending to people’s shared yet individually different experiences of social displacement during the Covid-19 crisis, when various controls were implemented at local, national and transnational borders. With her work, Shen implicates herself and viewers in a compelling material environment to reconsider and reconfigure the relation and demarcation between inside and outside, as well as home and the world.

On the other side of the French window (Fig. 2), suspended from the bamboo cane is a cobweb made of copper wire. On close inspection, a tiny copper spider comes into view. It is dangling on a long tendril as if it could climb back to the web at any time and continue the construction of its habitat. With this spider, Shen pays homage to a work made by her late husband—The Saint Learns from a Spider to Weave a Cobweb. In 1994, Huang put a live spider on a transparent glass panel which was attached to the bottom of a cage-like lampshade hanging from the ceiling over a desk. Under dim light, the spider crawled slowly, and its moving shadow was projected onto an unfolded book—the Chinese translation of Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp—placed on the desk. On various occasions, it appeared as though the spider was reading Duchamp’s words. The work poses a challenge to the authority of the artist in giving meaning and value to their work of art. By working with a live spider beyond human control, Huang underlined the work’s own capacity to express itself. This approach to art production is also evident in Shen’s practice. While recalling her own experience during the pandemic lockdowns, Shen gives agencies to her work to materialise situations of confinement, displacement and loss that are open to viewers’ embodied explorations.

Obviously, the floor is not quite the “appropriate” place where a window is supposed to be at home. The work, in this regard, gives rise to a sense of dislocation and perplexity. The dangling spider draws viewers into close proximity to envision situations of not only entrapment and helplessness, but also potential escape from the private household. When exhibited in “Angling”, the unsealed glass container, once filled with Paris air, was displaced from its original context and relocated to a different geographical location, which might contain fresh air from Beijing instead, forging embedded local connections beyond national and regional borders, no matter how insubstantial or unrecognised they appear to be. Inserted through the window opening, the bamboo cane brings to the fore an ambiguous, yet generative situation in which the demarcation between interior and exterior, personal and communal, as well as intimate and foreign that still more or less undergirds the oppositional construction of us and others; belonging and unbelonging becomes obscure.

In and via Shen’s work, seemingly inconspicuous everyday items all play their roles in engendering and enhancing situations of home in displacement. None of them is simply rendered as a fixed and stable object. Rather, they have been carefully arranged to foster a multiplicity of materially embedded and mutually affected relations among things and people. According to Puig de la Bellacasa, caring for a non-human without objectifying it can broaden the consideration of agencies of care that “circulate in interdependent more than human relational webs”.[16] With her work, Shen sheds light on the agencies of quotidian things to cultivate affinities and alliances that have rarely been acknowledged in the human-centred configuration of identity, home and belonging, provoking reflections on processes of inclusion and exclusion in ever-changing material forms beyond clear-cut dichotomies of self and other, as well as us and them.

Unlike Duchamp’s Fresh Widow, which is often displayed in a glass cabinet, Pêcher l’air de Paris is, as mentioned, placed directly on the ground. Viewers can observe and experience its material and spatial construction from different angles, generating their perceptions and understandings of an immediate surrounding environment that they share, inhabit and co-produce with Shen’s work. Wandering around the piece on the exhibition site, viewers are prompted to continuously position and reposition themselves “in place” without ever reaching a definitive conclusion in terms of whether they are included or excluded, confined or unrestricted. Far more complicated than clearly identified experiences of forced physical dislocation or confinement—the two most common conditions of displacement as discussed by Hammar—Shen calls forth viewers’ active and co-constitutive involvements in her work’s ongoing production of meanings, experiences and relationships through which situations of home and displacement could be variously evoked or configured with individual differences. Indeed, with Pêcher l’air de Paris, Shen also brings to the fore a complex of reciprocally formative relations between works produced by herself, her late husband and Duchamp across different geographical, socio-historical and cultural contexts that might not always be that comprehensible to all embodied viewers, especially if they are not provided with sufficient information. However, this could be exactly part and parcel of the typical experiences of displacement marked by immediate sensuous relatedness, in spite of uncertainty, perplexity and anxiety.[17]

Gazellez

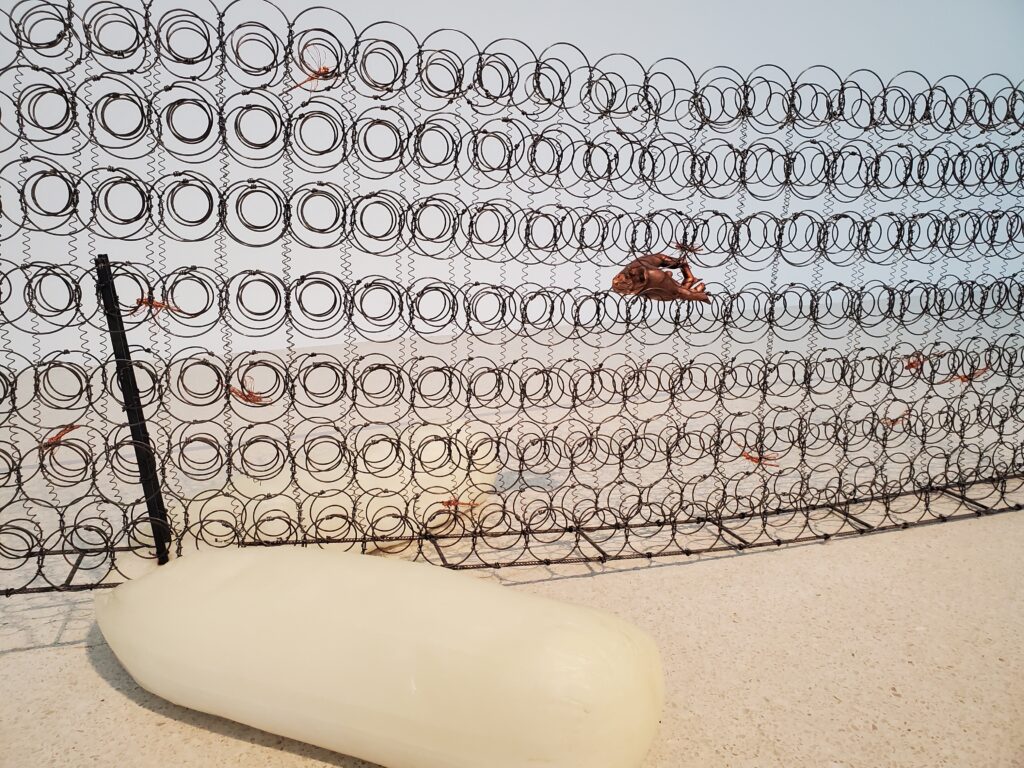

In another work presented in “Angling”, seemingly trivial and unremarkable household items are also altered and rearranged by Shen to destabilise people’s habitual perceptions of home and domesticity. Gazellez (1990–2020) takes its title from a student dormitory where Shen and her husband stayed for a short period of time before settling down in Paris. A wax cast of a long French pillow is located on the ground to hold up the vertically placed spring frame of a single bed (Fig. 3).

The work evokes not warmth and comfort, but dislocation, strangeness and unease. The wax pillow recalls the artist’s experience when residing in the student dormitory. At that time, Shen and her husband had to squeeze into a single bed every night. A long French pillow was used to extend the bed a little bit at one end and give them some extra space and support. The set of bedsprings was again found at a flea market in Paris, which, according to the artist, reminded her of the type of spring beds in the student dormitory.[18] Shen had been thinking about making a work with it for years. However, it was only during the Covid-19 lockdowns that the piece came into being. Although it was created in 2020, for Shen the production of the work could be considered to span three decades, since a specific past experience had been repeatedly and differently recollected and recreated in her mind over time.[19]

According to Hammar, displacement alters people’s relationships to “old and new places in terms of the loss of former social and material grounding, and subsequent repositioning and struggle for recognition and new terms of belonging.”[20] After her move to France, Shen was compelled to engender connections with/in an unfamiliar foreign context. At the time, a range of everyday items available in her surroundings were of great importance in (re)making herself at home beyond national and cultural borders. In Gazellez, the bedsprings and the pillow especially recall such intimate memories that Shen had with her husband when inhabiting their first home in Paris—their efforts to make the best use of things around them to create a relatively comfortable place of respite, no matter how temporary and makeshift it was. In stark contrast to the operational arrangements around (im)migrants by governmental authorities through apparatuses of assimilation and incorporation, which ultimately suppress differences and incompatibilities, Shen brings to light the quotidian private dimension of homemaking practices that could be conducted by individuals or families in remarkably divergent ways.

When exhibited, the set of bedsprings induces strong feelings of spatial transgression, prompting people to reconsider their bodily and social relations across a clear divide between interior and exterior. An intimate domestic item, a bed, which is usually concealed from view in public, has its internal skeletons exposed to intrusive investigations from viewers, while provoking reflections on issues of migration and relocation. In this regard, Shen’s work engenders productive situations of dislocation that disrupt established spatial binaries and hierarchies between local and global, and personal and social.

Seen from the side at close proximity (Fig. 4), the intersecting bedsprings appear very similar to wire mesh barriers often installed around places like prisons and border checkpoints, evoking situations of imprisonment and surveillance. Viewers can also bend over and look through the coiled bedsprings. In this sense, if the dormitory room gave Shen and her late husband certain forms of support alongside discomfort and roughness, Gazellez materialises a much more unsettling condition of home in displacement, since the distinction between inside and outside, private and public is completely overthrown. Given the time when the work was created, this could also be argued to speak to people’s experiences during the Covid-19 crisis, when domestic life and individual existence were unprecedentedly intervened in by official measures of control and regulation to prevent the transmission of the virus, albeit with dramatic disparities across countries and regions.

A sculpted female hand is embedded in the middle of the bedsprings (Fig. 5). It is a copper cast of a broken hand that the artist found in her husband’s studio after his passing.[21] The hand is one of the many moulds made of resin and clay for Huang’s Buddha’s Fifty Arms, which was first presented as part of the 1997 “Sculpture Projects Münster”. The work reinvents the iconography of the Buddhist goddess Guanyin with a thousand hands. The metal structure calls to mind Duchamp’s Bottle Rack (1914), enlarged multiple times and extended with arms and hands holding objects of Buddhist symbolism, such as a bell, a bow and a lotus flower, which are emblematic of wisdom, intuition and purity respectively. Moreover, there are also several commodity products, including a broom, a brush and a selection of silk scarves. With tangible items held in sculpted hands, Huang’s work stimulates viewers’ embodied sensuous experiences that provide concrete material grounds for spiritual beliefs, creative ideas and commodity symbols.

The hand likewise comes to the fore in a compelling material form in Shen’s work. Its embeddedness in the bedsprings obscures the clear division between body and object. At first glance, it appears polished and delicate. However, close inspection reveals that the top part of the fourth finger is relocated to the upturned palm. It is a cast of a broken mould, which is supposed to be discarded rather than preserved. With this broken hand, Shen implies the fragility and inevitable mortality of human bodies.[22] Meanwhile, several dragonflies, made of copper wire, rest on the bedsprings. It appears that they could fly through the spiral springs, endowing this skeletal bed mattress with liveliness. In this way, Shen’s work provokes reflections on the intricate cycle of life and death.

Several pieces presented in “Angling”, such as Pêcher l’air de Paris and Gazellez, are reminiscent of the works by the artist’s late husband. Nonetheless, Shen has been very cautious about any reductive reading of her practice as an expression of personal sorrow and grief, which, for her, could preclude viewers from experiencing the work’s rich and affective material configuration that continuously engenders meanings and relationships.[23] Therefore, the various associations that recall Huang’s works are made very subtly, and grounded in broader circumstances of transnational migration and the Covid-19 crisis. When encountering Gazellez, viewers are not provided with all the details of the background stories related to the artist’s personal life. Instead, they develop perceptions and understandings based on their on-site engagement with the pieces, which do not always resonate with the artist’s reflections on her personal loss and struggle through art practices.

Apart from the vertically placed bedsprings, which enable viewers to see through an everyday item, the work also fosters co-affective connectedness with/in the immediate surrounding environment of art production and reception. The wax pillow emits a very light scent. Against internal light, the full shadow of the work—including the bedsprings, the hand and dragonflies—is projected onto the ground and occasionally intersects with the moving shadows of viewers. Because of this, Shen’s work creates a strong sense of place attachment predicated on people’s kinaesthetic and multisensory involvements, even though it induces palpable feelings of dislocation and disquiet.

With her work, Shen transforms things into “matters of care”, which, according to Puig de la Bellacasa, demonstrate “a way of relating to them, of inevitably becoming affected by them and of modifying their potential to affect others.”[24] Puig de la Bellacasa’s discussion is developed from Bruno Latour’s notion of “matters of concern”.[25] In his writing, Latour proposes to collapse the critical distance typical of scholarly works, calling on researchers as knowledge creators to attend to their inextricable and formative engagements with the continuing (re)construction of the reality of matters of fact.[26] To extend matters of concern to care, Puig de la Bellacasa highlights people’s affective and ethical involvements that intensify, complicate and diversify the relational mattering of things, facts and the world.[27] As for Gazellez, both artist and viewers take part in the work’s iterative configurations of home in displacement with differences. By stimulating viewers’ embedded contributions to her work’s lively becoming(s) that do not necessarily align with what she cares about and cares for, Shen’s practice fosters the continuous multiplication and prolongation of vibrant and generative human-nonhuman entanglements. In this sense, the work is left very open for viewers to make their own associations with varied authoritative powers and controls that regulate human bodies through systems of surveillance and confinement. Meanwhile, at times it is the inability to fully comprehend or align with the concerns and experiences of others that sheds light on our caring and responsive relatedness with/in multiple interdependent worlds, both human and beyond, without over-identifying with any forms of life as easily graspable objectified conditions.

Fragments de mémoire

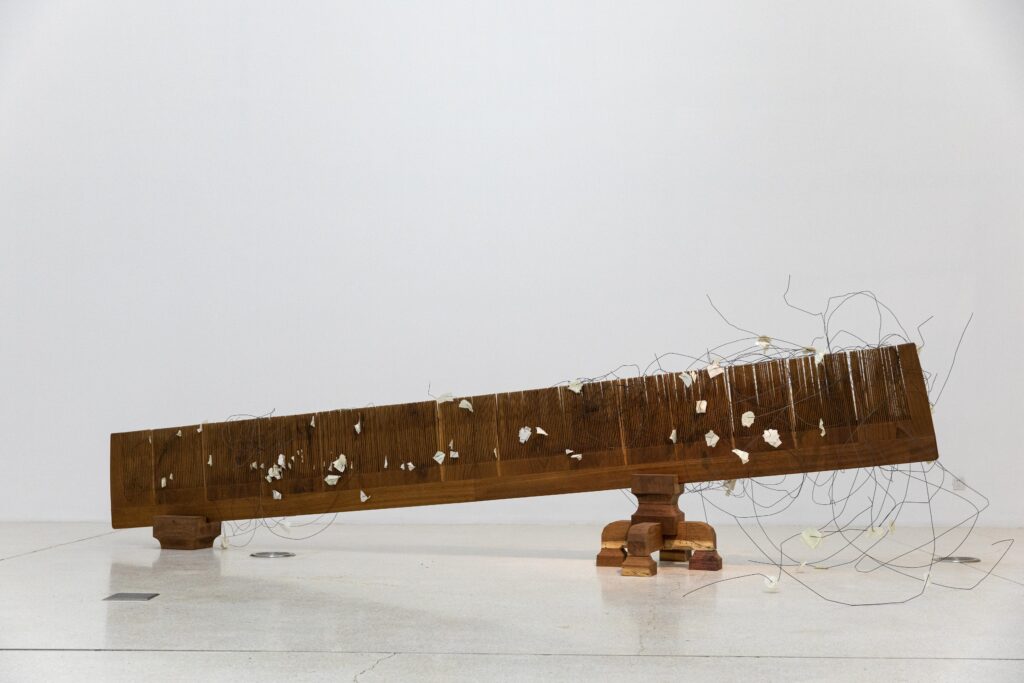

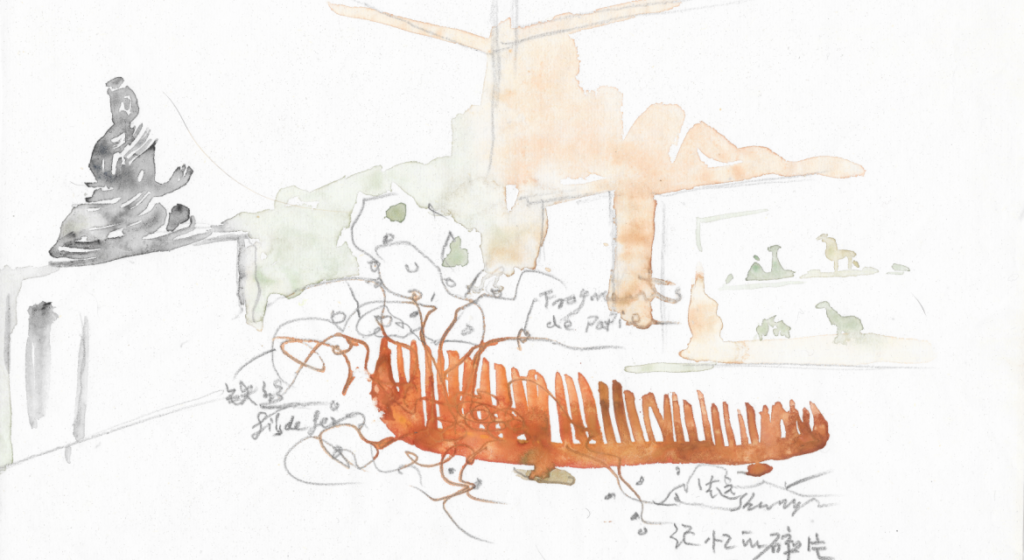

Shen explores and demonstrates the affective agencies of quotidian things to cultivate connections and produce knowledge across times, places, languages and cultures. In what follows, I will push further the investigation of this dimension of Shen’s practice with Fragments de mémoire (2019). The main part of the work is an enlarged wooden comb (Fig. 6). Its bottom end is inserted into the slots of two display stands. Across the comb’s teeth are long iron wires, which look as if hair was left on the comb, evoking human bodies in absence. Some of the wires extend to the ground, inducing viewers to come close while generating a mild disturbance around their feet. Scraps of paper are found here and there between the comb teeth or on the wire. In a way, they resemble light dandruff that is brushed away every day from one’s scalp (Fig. 7). The paper is the typical type widely used by people in mainland China during the 1980s and 1990s to correspond with family members or friends before the prevalent use of telephones.[28] In this sense, the paper pieces recall the artist’s experiences of writing letters back to China after her move to France.

For Shen, hair and dandruff are bodily detritus that carry lived experiences and memories.[29] Enlarged to the same proportion as the comb, the iron wires and scraps of paper, which are emblematic of the inconspicuous debris of a living past, could hardly be ignored by viewers. Thus, Shen’s work compels people to carefully consider the meanings and values of those seemingly trivial, but tangible traces of past lives that would otherwise be discarded or neglected. Along with other works presented in the show, the piece communicates the fear of forgetting when dealing with situations of loss and displacement, whether caused by cross-border migration, bereavement or forced social distancing over the course of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Meanwhile, it is worth noting that the work was originally commissioned in 2019 by the Cernuschi Museum (Musée Cernuschi) in Paris. Shen was invited to create a work to forge dialogues with the museum’s rich Asian art collections. During the site visit, Shen coincidentally encountered several ancient wooden combs kept in glass cases. For Shen, they carry personal memories and bodily traces that could hardly be retrieved through the present museum display.[30] Eventually, she came up with Fragments de mémoire (Fig. 8).

The work evokes memories and experiences of cross-border movement and relocation, while extending her enquiries to the displacement of art and artefacts that play a part in transnational and transcultural knowledge production. However, due to the lockdowns and the museum’s renovation plans, the work was not presented to the public until autumn 2021. When shown at the Cernuschi Museum, Fragments de mémoire was located in the high-ceilinged central hall in front of the Buddha of Meguro (Fig. 9)—one of the thousands of art objects, particularly Japanese and Chinese bronzes, taken back by the founder Henri Cernuschi following his extended tour of the Far East in 1871 and 1872. After returning to Paris, Cernuschi built his mansion home to house his large collection of Asian art and artefacts. On a regular basis he also hosted dinners, parties and balls to bring together artists and art lovers. According to art historian Ting Chang, the mansion at the time created “an exotic spectacle for entertainment”.[31]

The collected works were displayed by Cernuschi as purely aesthetic objects, which introduced foreign designs and techniques that played a role in stimulating the development of French arts and crafts.[32] The religious and ritual functions of these items in the original contexts where they were found, as well as the actual conditions of Cernuschi’s acquisition—his privileged status as a European collector that enabled him to purchase and remove sizable works in Asia and ship them back to Europe—were barely acknowledged.[33] Moreover, with a specific focus on aesthetic development in the arts and visual culture, Cernuschi’s displays generated no concrete local connections with people’s everyday life experiences, even though they were housed in a domestic setting. Basically, the various regions and countries that he visited through his voyage to the Far East were all reduced to an aesthetic style of Asian art and design.

After his death in 1896, Cernuschi bequeathed the mansion and its rich content to the city of Paris to establish a museum of Asian art. Since its inauguration in 1898, the museum has gone through multiple considerable renovations to expand and redesign the exhibition areas to modern standards, and its major collections have been further strengthened and enriched. Nevertheless, when exhibited, most of the items are still cloistered in display cases or located on pedestals. They are largely shown as knowable objects with printed labels, indicating their specific regional, national and historical provenances. In this sense, I would argue that the collections at the Cernuschi Museum tell histories of displacement in which the complex geopolitical and socioeconomic networks of domination and subjugation—or more specifically, the asymmetrical power relations between Europe and Asia that are inseparable from the imperial past of expansion and acquisition—are left irretrievable through the items on display. This is quite a far cry from the relational approach to displacement as explored in Shen’s work. Viewers could hardly develop any understandings or interpretations other than the passive reception of a particular historical perspective on Asian art and aesthetics that, in effect, manifests and reinforces, in Chang’s words, “political, economic and colonial hegemony” of European empires.[34]

By contrast, taking the form of personal things, Shen’s work sheds distinctive light on the intricate interrelation between memory, history and lived experiences. According to the artist, “the rich collections at the Cernuschi Museum hold countless stories about the past, even though they are not always visible and knowable to viewers. My installation tends to add a new object—a new story constituted of memory fragments, which allows viewers to make their own connections and form their own understandings of histories.”[35] Compared with the work’s display in “Angling”, the dialogic engagement with the setting of the Cernuschi Museum adds another layer of meaning in Shen’s exploration of displacement.

For Shen, a thin flat comb is easily carried around when people engage with cross-border travel or migration.[36] Used on a daily basis, it evokes an embodied form of presence even in conditions of movement and displacement. Enlarged more than 20 times the usual size of a comb, Shen’s work impinges on the viewer’s space, compelling reflections on the appropriate viewing distance people need to keep when encountering museum displays. It engenders feelings of displacement and estrangement as a familiar personal item becomes strange. Meanwhile, Shen’s work, hardly identified with any particular time and place, also appears incompatible with other items exhibited at the Cernuschi Museum that are primarily organised based on strict chronological and geographical divisions.

Both hair and dandruff could be considered very intimate bodily elements, inducing discomfort and repulsion if they belong to unknown others and come into our proximity. Fragments of personal memories and bodily experiences, which are rarely taken into consideration in the construction of museum collections and relevant displays, come to the fore in Shen’s practice to activate viewers’ engagements at a very intimate sensuous level. In this way, the artist heightens the viewers’ embedded inside-ness and within-ness in the production of meanings, histories and knowledge without negating differences and discrepancies. With her work, Shen indicates no direct critique of the display format at the Cernuschi Museum. Rather, her practice puts forward ways of thinking, knowing and doing with care that cast light on the interdependent relationalities of things and people concealed in the museum’s construction and presentation of Asian histories and cultures via art and artefacts.[37] As scholars such as Sandra Dudley and Ken Arnold have indicated, over the last hundred years of development museums have “forcibly separated objects from every one of our senses except sight.”[38] In this regard, I would argue that Shen’s work makes an intervention by reinventing the sensory dimension of knowledge production often lost in the museum practices.

In addition, the fallen hair and dandruff evoked by Shen’s work could be perceived as corporeal remnants displaced from the displaced. Fragments de mémoire could therefore be argued to forge generative situations of thinking with marginalised otherness, while avoiding the appropriation and objectification of any people, places and cultures.[39] With her work, Shen configures otherness in and via tangible and affective relationships that are heightened through viewers’ various embodied experiences within the context of the exhibition. According to Puig de la Bellacasa, “thinking with care compels us to look at thinking and knowing from the perspective of how our cuts foster relationships”, spawning specific configurations of the world based on the fact that we all care for some things other than others.[40] However, what is cut off or displaced can also foster alternative caring relations that hold potential to expand and reformulate the current assemblage so as to lead to the world’s iterative differential becoming(s). Despite nuanced forces of repulsion and unease, by cultivating embodied connections with displaced otherness in tangible material forms, Shen’s work brings to the fore ways of being and relating that take care of what is often ignored, neglected or excluded. This makes it possible to unsettle, enrich and rework the constitution of identities, histories and cultures beyond existing knowledge systems.

Coda: Decolonising the Art of Displacement

In Shen’s practice, personal experiences of displacement have been extended to a wider socio-political and cultural context to reconsider and recreate one’s caring connections with things, people and places that unsettle and transgress the hierarchical binary divisions between belonging and exclusion, local and foreign, and centre and periphery. This reveals an important decolonial dimension of Shen’s artistic practice of homemaking in displacement, which, building on as well as departing from Hammar’s writing, dislodges not only human bodies but also a variety of orders, systems, and power relations that underpin the persistent hegemony of the Global North in the production of knowledge and discourses around nations, cultures, histories and otherness.[41]

Whereas Hammar describes her relational conception of displacement as “a Southern-driven approach with general relevance” beyond Africa and the Global South, Shen explores the relational conditions of displacement by virtue of the affective material construction of her works of art.[42] In her work, Shen creates situations of material interdependencies concomitant with, in Puig de la Bellacasa’s words, iterative “category transgression” and “boundary redefinition” without negating dissent and resistance.[43] Neither Hammar’s writing nor Shen’s art demonstrates a decolonial position by simply subverting the hierarchy of an existing binary opposition, such as North and South. Instead, they make interventions by fostering thick and intricate relationships through which a range of geographical, socio-historical and cultural parameters that frame and shape people’s understandings of their surrounding worlds can be reinvented and reconstituted continuously and variously.

Furthermore, the decolonial dimension of Shen’s work could be also considered in relation to the recent calls to decolonise art history, as well as the production and exhibition of art of displacement—works made by artists with multiple migratory backgrounds to reflect on individual or collective experiences. In 2020, the leading academic journal Art History published a selection of written responses from art historians, curators and artists to a series of questions about decolonising art history. In connection with her research on contemporary Southeast Asian art, art historian Pamela Corey underlines the importance of of decentring “the West” within the discipline. In the meantime she also warns about the constricted identifications of artists and their works still “installed by colonial regimes, nationalist historiographies and developmental discourses” which have led to many so-called decolonial practices that are actually “misconstructed through ill-conceived diversity initiatives”.[44]

Corey’s discussion calls to mind scholarly debates around the institutional apparatuses of multiculturalism from the early 1990s onwards in Euro-American contexts and beyond. Highly influenced by the development of postcolonial studies in the 1980s, artists with divergent migratory and diasporic backgrounds started to create work to combat exclusion and displacement, and to seek “recognition of minority and migrant cultures and identities”.[45] In response, multiculturalism, as a complex of ideologies and inclusive policies, became an important curatorial strategy widely applied by art institutions to accommodate cultural diversity and hybridity. However, as scholars like Sarat Maharaj, Anne Ring Petersen and many others have pointed out, institutional attempts at multiculturalism still led to specific identifications and classifications of artists and their works for the sake of managerial convenience.[46] Through art and exhibition-making, different cultures have often been juxtaposed with one another as static and discrete entities that are suspended from the intricate relational possibilities of connectedness, affiliation, tension and discord.

Although most of Shen’s works are modelled on objects that are part of her everyday surroundings, none of them are explicitly identified with a confined national or cultural environment. Instead, by attaching importance to the personal, the bodily, the quotidian and the affective, Shen reveals the inevitable partiality and contingency of knowledge production closely related to the ongoing (re)formation of histories and cultures. In this regard, I would argue that Shen’s works make it possible to disrupt and decolonise the institutional construction of difference and otherness based on constricted and reified cultural categories through which certain residues of colonial practices still come to the fore. Through the analysis of Shen’s works, this article extends and enriches existing scholarly works on diasporic art and cultural practices, which, according to Kobena Mercer, undermine “the monologic exclusivity on which dominant versions of national identity and collective belonging are based.”[47] Shen’s artistic practice of homemaking is not limited to forging a sense of connectedness that contests and destabilises established national and cultural boundaries often associated with art of displacement. More importantly, cultivating caring relationalities among things and bodies, Shen’s work sheds light on people’s embeddedness in and interdependence with the wider more-than-human world, offering distinctive perspectives to consider and configure affinities and alliances with otherness beyond categorical boundaries and hierarchies ingrained in human societies.

Footnotes

- Shen, Yuan. Zoom meeting with author on 2 October 2021. ↑

- Hammar, Amanda. “Introduction: Displacement Economies in Africa”. In Displacement Economies in Africa: Paradoxes of Crisis and Creativity. Amanda Hammar (ed.). London and New York: Zed Books. 2014. pp. 8-9. ↑

- Ibid., p. 3; Hammar, Amanda. “Displacement Economies: A Relational Approach to Displacement”. In The Handbook of Displacement. Peter Adey et al. (eds.). Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. 2020. pp.67–74. ↑

- Hammar, “ Displacement Economies”, p. 74; Hammar, “Introduction”, p. 7. ↑

- Hammar, “Introduction”, p. 16. ↑

- Ibid., p. 3. ↑

- Hammar, “Displacement Economies”, p. 74. ↑

- Shen in Ting, Selina. “Shen Yuan–Women Artists and Intimate Space”. InitiArt Magazine. 11 March 2010. Available at https://initiartmagazine.com/2010/03/11/shen-yuan/ (accessed 2022-06-09). ↑

- Puig de la Bellacasa, María. Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More than Human Worlds. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. 2017. ↑

- Ibid., p. 6. ↑

- Ibid., p. 70. ↑

- Puig de la Bellacasa, María. “‘Nothing Comes Without its World’: Thinking with Care”. The Sociological Review. vol. 60. no. 2. 2012. p. 198. See also Barad, Karen. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement Agential Realism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. 2007. p. 183. ↑

- Friedberg, Anne. The Virtual Window: From Alberti to Microsoft. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 2009. p. 124. ↑

- Edson, Laurie. Reading Relationally: Postmodern Perspectives on Literature and Art. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. 2000. p. 130. ↑

- Hammar, “Displacement Economies”, p. 69. ↑

- Puig de la Bellacasa, Matters of Care, pp. 24, 83; See also Bennett, Jane. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham, NC: Duke University Press Books. 2010. p. xii. ↑

- See Feather, Howard. Social Theory of Displacement: Adventures in the Everyday. London: Austin Macauley Publishers. 2024. pp. 33–34. ↑

- Shen, Yuan. Interview with author on 18 May 2023. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Hammar, Introduction. 15. ↑

- Shen, Interview 18 May 2023. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Puig de la Bellacasa, “Matters of Care in Technoscience: Assembling Neglected Things”. Social Studies of Science. vol. 41. no. 1. 2011. p. 99. ↑

- Latour, Bruno. “Why Has Critique Run out of Steam? From Matters of Fact to Matters of Concern”. Critical Inquiry. vol. 30. no. 2. 2004. p. 231. ↑

- Ibid., pp. 231–33. ↑

- Puig de la Bellacasa, “Matters of Care in Technoscience”, pp. 88–90. ↑

- Shen, Interview 18 May 2023. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Shen, Yuan. Interview with author on 13 November 2024. ↑

- Chang, Ting. “Collecting Asia: Théodore Duret’s Voyage en Asie and Henri Cernuschi’s Museum”. Oxford Art Journal. vol. 25. no. 1. 2002. p. 33. ↑

- Ibid., 32. ↑

- Ibid., 32-33. ↑

- Ibid., 32. ↑

- Shen, Interview 18 May 2023. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- As for scholarly discussions regarding the construction of imperial archives and museum collections, see Richards, Thomas. The Imperial Archive: Knowledge and the Fantasy of Empire. London: Verso. 1993. pp. 1–10. ↑

- Dudley, Sandra. H. Displaced Things in Museums and Beyond: Loss, Liminality and Hopeful Encounters. London: Routledge, 2020. p. 111; Arnold, Ken. “Review of Elizabeth Edwards et al. (eds), Sensible Objects: Colonialism, Museums and Material Culture, Berg 2006”. Museum and Society. vol. 7. no. 3. 2009. p. 211. ↑

- See Puig de la Bellacasa, “Nothing Comes Without its World”, pp. 199–202; and Sliwinska, Basia. “Caring to Notice: Sera Waters’ Disentangled Pasts, Attentive Reparation and Truth-Telling Toward Survivable Futures”. Art Journal. vol. 82. Nno. 4. 2023. p. 22. ↑

- Puig de la Bellacasa, “Nothing Comes Without its World”, p. 204. ↑

- Hammar, “Introduction”, p. 17. ↑

- Hammar, “Displacement Economies”, p. 74. ↑

- Puig de la Bellacasa, “Nothing Comes Without its World”, p. 201. ↑

- Corey, Pamela N. “Decolonizing Art History”. Art History. vol. 43. no. 1. 2020. p. 19. ↑

- Petersen, Anne Ring. Migration into Art: Transcultural Identities and Art-Making in a Globalised World. Manchester: Manchester University Press. 2017. pp. 55–56. ↑

- Ibid.; Maharaj, Sarat. Interviewed by Daniel Birnbaum. “In Other’s Words”. Artforum. vol. 40. no. 6. 1 February 2002. p. 110. ↑

- Mercer, Kobena. Welcome to the Jungle: New Positions in Black Cultural Studies. New York & London: Routledge. 1994. p. 66. ↑