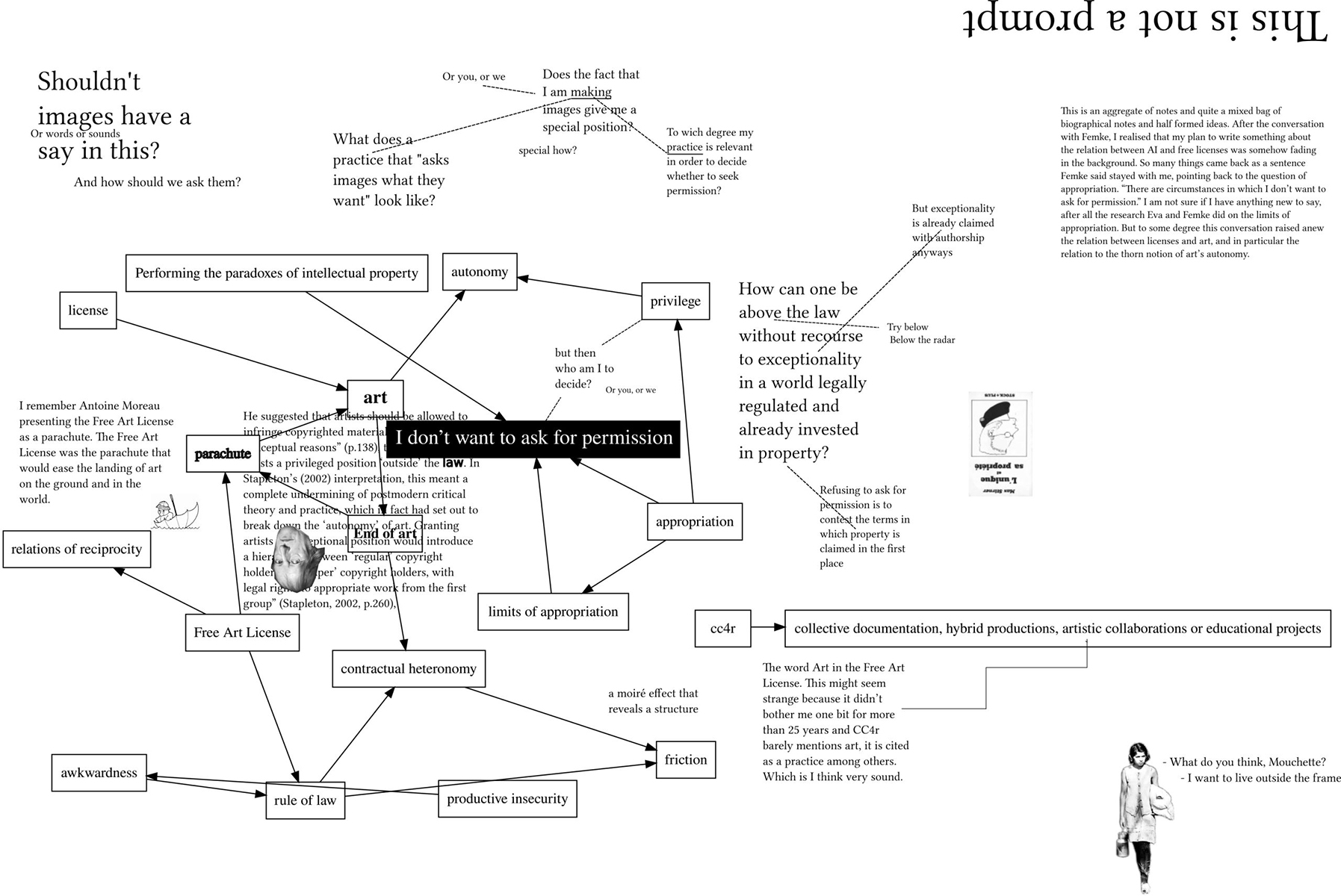

This section contains a set of polyvocal provocations that address universalisms in Free Culture and Open Access. These prompts were originally commissioned for the work session “Revisit Reuse”, then partly rewritten to make them relevant to multiple contexts. They point towards potential gaps in the ways we practise reuse and purposefully aim to trigger the reader to consider a specific angle. The prompts in this section take many forms and shapes, from questions to games, from scores to mixtapes, drawings, diagrams, collages and letters. They invite a response, and act as devices to make something happen.

Prompt: Prepositions

Séverine Dusollier, a long-time collaborator of Constant and inspiring conversation partner for thinking about critical approaches to copyright and intellectual property, trained as a lawyer and works as a researcher and teacher in Paris. With her persistent work on collective authorship, inclusive property and attribution otherwise, she brings a perspective to the project that is grounded in legal practice. Séverine sent us several prompts after we met for an afternoon to record the conversation “Subverting the narrative of property“.

In the prompt ”Prepositions”, originally developed for the work session “Revisit Reuse“, she proposed us to reconsider how copyright sets up particular relationships with creative works, asking whether changing singular pronouns into plural pronouns would be sufficient to move from individual genius to collective practices.

Building on Séverine’s suggestion to think through the performativities of language to broaden our imagination for the kinds of relationships that could exist around creative works, we decided to focus on how we articulate semantic roles in time, space and directionality. Riffing on her game with prepositions and pronouns, this prompt invites the reader to experiment with a range of combinations that each open up to different possibilities for relating to a creative work.

Prompt: Do First Times Exist?

In October 2023, Femke and Eva organised an event at Göteborgs Litteraturhus that they decided to call “First Times Do Not Exist” referencing a quote from Mexican author Cristina Rivera Garza’s book on disappropriation. We invited Jen Hayashida and Nkule Mabaso to speak about their practices of translation and citation. They both responded to the title in very different ways, and we are interested in the friction between these two approaches.

Jen talked about translation as a practice of reuse, reflecting on the position of the translator in relation to the text. She made clear that for her a “transhistorical awareness” is needed for the author/translator not to behave in a settler way, as if they were the first on the scene.

Nkule enters the scene from a different position, stating that first times may not exist, but that there is always a first time for you. She therefore focuses on how she enters the scene through her own horizon of experience. This allows her to cite and reuse with integrity.

Could we imagine a practice in which both perspectives coexist?

Jen Hayashida (20:07)

I think it’s a temporal question, which is also at the heart of your title for this event, “First Times Do Not Exist”. Because this notion that you’re the first person entering the story is incredibly relevant now: do you call something a defence, or do you call it an attack? What is the translator’s position in relation to the text? If the translator imagines that they are the first person there, as a kind of settler, then that makes me suspicious. The same is true of the author, obviously. If the author has a stake in their writing, where they want to be able to claim that they are the first person on the scene, then that to me is something that puts me on alert. As a translator, I think it’s imperative to be mindful of the fact that you’re never the first person on the scene, to treat the language and the claims of the text with that kind of transhistorical awareness.

Listen to Jen Hayashida

Nkule Mabaso (14:13)

Yeah, so I’ll pass the publication around. I don’t know if it helps anything to see it because the issue is not there. The issue is somewhere else. The issue is a third site, [it lies] somewhere else, in the connecting space, [in the malformed] synapses that draw these things together. And the way I tried to approach it—since I work quite collaboratively all the time—and the title of today is “First Times Do Not Exist”— I guess, yes, there is no first time, but there is a first time for you. When you encounter something, and that thing catalyses something, how do we then cite and make space for that moment of encounter? How do we make an acknowledgment of: “This thing that happened, catalysed my thinking in this way.” What would be an adequate way of signalling that?

Listen to Nkule Mabaso

Prompt: Collective Agreements

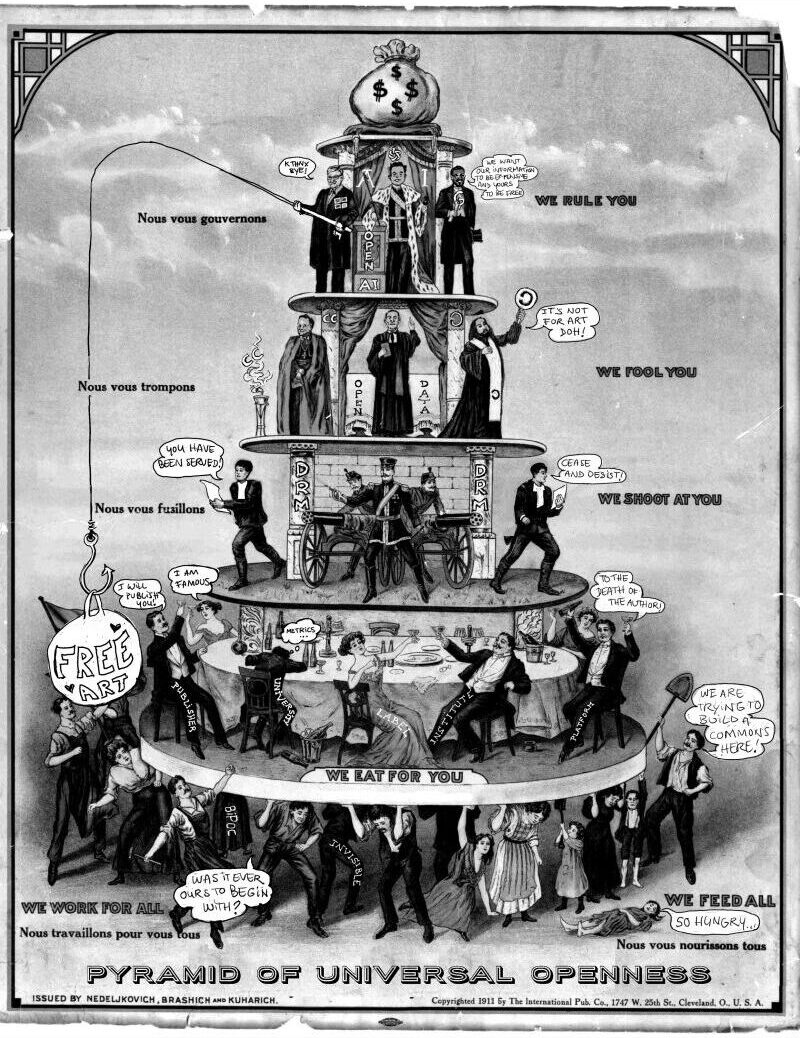

This prompt takes on Gary Hall’s blogpost “Experimenting with Copyright Licences“1 in which he ponders what the right licence would be for an experimental and collectively written book he is involved in. Comparing the Open Content licence “Creative Commons (CC)” with “Collective Conditions for Reuse (CC4r)“, he argues that both propositions might put too much agency with individual (human) users, and therefore contribute to individuating processes rather than advocating for collective agreements and foster reuse as a relational practice.

Analysing Creative Commons licences, usually associated with Open Access publishing, he states that these are not “actually concerned with producing a common stock of non-proprietary spaces and resources, along with the collective social processes that are necessary for commoners to produce, manage and maintain them and themselves as a community.” The decision-making, Hall wonders, may happen “too much at the level of the specific actors concerned—be they individuals or collectives (in CC4r’s case)—and on what they are persuaded is the right thing to do?”

What kind of collective conditions could nurture reuse as relational practice, rather than counting entirely on individual responsibility? How could they contribute to collective social processes that produce, manage and maintain a community?

Expanded Prompt for PARSE and Revisiting CC4r

Creative Commons (CC) is a North American non-profit organisation that provides an array of relatively simple licences from which individual human creators (or their community stand-ins) can choose if they wish to grant permission for others to share and reuse their work under copyright law. These licences can then be applied to creative goods, such as books, which are understood as being ontologically distinct from humans. CC licences range from the most restrictive “Attribution-Non-Commercial-No-Derivatives” licence (or “BY-NC-ND”) to the least restrictive Attribution licence (or “CC BY”).

It is estimated that there are now over 1 billion CC-licensed works. Yet for all this apparent success, a fundamental problem with Creative Commons and its idea of commons remains; namely that despite its name, CC is not actually concerned with establishing commons at all, creative or otherwise.

This is apparent from the way it prioritises safeguarding the rights of copyright holders over their creative work, as opposed to assigning rights to prospective users. Included in this is the right of holders to choose from CC’s six different types of licences according to what they consider to be most appropriate for them, plus its CC0 public domain dedication by which they can decide to relinquish their copyright. “Only the copyright holder or someone with express permission from the copyright holder can apply a CC licence or CC0 to a copyrighted work”.2 The requirement that a licence can only be applied by the copyright holder or their representative means Creative Commons is ill-suited to work that is collectively produced in the first place, as is the case in some indigenous communities, and for which there may not be an original, identifiable copyright holder.3

The underlying liberalism and individualism on display here is another feature of Creative Commons that makes plain its lack of interest in creating commons. Rather than championing a collective understanding or philosophy of creativity and copyright, CC merely offers a range of “simple, standardised”, some-rights-reserved licences that sovereign human creators can freely select from, again “on conditions of [their] choice”, according to what best suits their needs.4 Consequently, Creative Commons is not actually taken up with establishing a shared pool of non-proprietary spaces and resources that everyone can access and make use of on equal terms, even though that is the most common interpretation of commons. An emphasis on the normative frameworks and principles of governance that best enable the management and maintenance of such shared spaces and resources is what underpins liberal attitudes to commons, such as those of Elinor Ostrom and Yochai Benkler. The neoliberal equivalent sees free marketeers regarding commons as an alternative to state regulation and centralised bureaucracy.

Nor is Creative Commons concerned with prioritising the collective social relations that are necessary for commoners to jointly produce, manage and sustain these resources and themselves as a community. It is the focus on collective social relations that is central to more radical approaches, such as those of Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, or Fred Moten and Stefano Harney, which emphasise constructing commons on the basis of shared political principles and practices, including those of the “undercommons”. From this perspective, commons offer a progressive alternative to capitalism’s privatisation, commodification and corporate trade.

Instead, Creative Commons has its basis in the idea that, legally, any original work created by a singular human author belongs to them in the first instance as their intellectual property. To be clear, this is not an accident, it is very much by design. To recast the words of open-source architecture advocate Carlo Ratti, it ensures that, while a certain “flexibility, evolution and adaptation” are possible, the “powerful impetus of human motivation remains intact: acknowledgment of authorship”.5

Gary Hall, July 8, 2024

Notes

- Gary Hall, “Experimenting with Copyright Licences” (20 April 2023). ↑

- Creative Commons. “About CC Licences”. Creative Commons. 2023. ↑

- For a range of Traditional Knowledge and Biocultural Labels that provide Indigenous communities with practical tools for managing, sharing and protecting digital cultural heritage in relation to copyright concerns, see Local Contexts. ↑

- Creative Commons. “Share Your Work”. Creative Commons. 2023. ↑

- Ratti, Carlo with Claudel, Matthew. Open Source Architecture. London: Thames & Hudson, 2013, p. 86. ↑

Prompt: Rebeing

In Towards a Lexicon of Usership1, Stephen Wright proposes to intervene in day-to-day language of “use” in order to change our understanding of what “use” could entail. When we asked him about a prompt to revisit reuse, he came up with the following playful script. The exercise is accompanied by “Re:Re:Re:Re:Re:Re:Re:Re:Ontology”, an introductory text that is included on this page. You can also download the PDF.

Rebeing: A Practical Exercise in Psycholexicography

In your mind, go through the entire alphabet from A to Z choosing as quickly and spontaneously as possible one verb per letter, prefixing each selection with re-, writing the verbs down as you go. Repeat twice for best results. A second list will rejig the same imaginary, just a little deeper. The third, a little deeper still.

Here’s Stephen’s first list, which we printed and installed for “Revisit Reuse”, as an example.

Re:Re:Re:Re:Re:Re:Re:Re:Ontology

In our former lives, we have all been earth, stone, dew, wind, fire, moss, tree, insect, fish, turtle, bird and mammal.2

Restarting All Verbs with Re-

One might well imagine a verb dictionary in which all the entries begin with re-. Frontloading all verbs—including verbal nouns and gerunds—in the language with this little prefix might usefully draw attention to the fact that when you get right down to it all use is reuse, all breathing rebreathing, all verbing reverbing. As thought-provoking as this retooled dictionary would be—or thought-reprovoking—it would also ultimately be redundant for, paradoxically, it suggests that all verbs have an embedded prefix anyway that we had previously failed to notice and was just being pointed out. In other words, it implies that the initiative allegedly performed or expressed by any given verb is somehow a re-initiative, and all performance re-performance, all doing redoing, all reading rereading, all discovery rediscovery, all action reaction. Indeed, the dictionary’s conceit seems to invalidate the very conditions of possibility of an event taking place at all, since it inscribes action itself in an endless web of causal factors. In philosophical terms, this re-dictionary would seem to make an outrageous ontological assertion: that being is rebeing, and that to be is to re-be. On the face of things, that is something that sounds not only nonsensical but infuriating. Inasmuch as it strips us of the very possibility of originating anything absolutely afresh, it insults our self-image as agents of creative authority and authorship. And it does so through language usage itself, which feels predominantly calibrated to uphold the constituent subject—the cogito upon which pretty much everything else is contingent. Re- is a common prefix, and very much a subaltern one, for those who rely on linguistic hand-me-downs. Recycling may be praiseworthy, but it is linguistically sentenced to entropy.

Relooping Reuse

Still, the fact that any verb, gerund or gerundive whatsoever can be put into an infinite loop merely by prefixing it with re- is intriguing. Though such usage may be jarring to the ear, it remains grammatically irreproachable. Perhaps it’s jarring because a language-immanent value system has habituated us to proceeding otherwise, and as we get used to the repeating logic of re-, a more complex web of morphing reuse will become perceptible. At any event, it is also true that many common verbs take easily to the prefix re-. For instance, any verb expressing some sort of recombinant action involving a pre-existent set of component parts or ingredients: reuse is spontaneously more logical than use, repurposing clearer than purposing, retooling truer to life than tooling. Or what about activities that follow the rhythm of the seasons or the recurrent cycles of life? Rebuilding, replanting, repairing, reproducing…

Refarming the Lifeworld

Let’s take things a step further. Like ancestral epistemologies, recent ecosystemic theory has drawn attention to the intractable connectedness of everything. All lifeforms and agents are endlessly remade from one another—what else, indeed, could they be remade from? We are all one, redistributed; forever remade, reformed, remixed, recoded, reintroduced, renamed, endlessly part and parcel of one another. The breath you just exhaled is already mine, for a moment; breathing is rebreathing is refarming the atmosphere. To live together in a biosphere is to remake use—or make reuse—of that atmosphere, of all that it is and all that is in it. Same goes for any landscape, literal or figurative. To even mention such a thing should be redundant—a statement of the obvious. That it clearly isn’t says something about the ideology embedded in use in general, and in language use in particular. This suggests there is something quite profound, from an ontological perspective, about reuse—and about the community of (re)users that make use and reuse. Let’s consider this from the point of view of language (re)use.

Redistributed Reuse

Meaning—all the meaning there is in the world, and by extension, all the tentative stability it provides—is generated, modified and upheld within language by the community of users of that language. Meaning results from a conflictual relationship between speech and language, between potentiality and power: individual usage (speech acts) may challenge or subvert collective usage (the institution of language), but if it challenges it too much, it strays from the realm of the collectively admissible and fails to take hold in language; conversely, if usage blandly reasserts the norm, innovation founders and meaning grows brittle. This means that as users of language, we are collectively entrusted with both upholding and renewing meaning—all the meaning there is. That’s a daunting task, though it is sufficiently redistributed so as to make it manageable. Language, though, is paradigmatic in another way too: since no one user invented language—which was always already available for use—we might as well say that in circular fashion language invented its users. This means, though, that it is logically inconsistent to speak of simply using language inasmuch as every component of it has already been reused, countless times over in countless permutations, and hence that there is only language reuse, making of us not users but quite literally reusers.

A Reassuring Ontology

Here language reuse can be seen as the paradigm of reuse in the broadest sense. Modernity contrived of many ways to put us humans on a higher plane than other lifeforms, but reuse would seem to put us all on an equal ontological footing: as reusers of the conditions for reproducing life itself, we find common ground with a planetary reusership. Ontologically, it’s very reassuring.

Notes

- Wright, Stephen. Toward a Lexicon of Usership. 2013. ↑

- Énard, Mathias (2023), requoting Thich Nhat Hanh, requoting the Buddha. ↑

Prompt: Fortune Teller

This prompt was developed by colleague and friend Cathryn Klasto from conversations, notes and diagrams connected to the event “First Times Do Not Exist” in Gothenburg. In search of a different mode of address to licencing and contracting, Cathryn developed the Fortune Teller device as an invitational gesture that can be dialogic and relation-making, can encourage action and thought, is not overly complicated, and easily (re)used and circulated.

→ See also Prompt: Do First Times Exist?

Cathryn invites you to download, print, cut out and fold the Fortune Teller device in order to find out whether “CC4r is for you”. You are prompted to engage with the different literal and conceptual unfoldings, which don’t take a singular form but offer a multitude of openings following the axis of (non)originality, implication, (non)ownership, courage, (non)binary and responsiveness.

Download Fortune Teller template

Prompt: re:re:re:er:ri mixtape

Erri Ammonita share four stories about selected songs copied on 19 used cassette tapes decorated with found letters. The stories printed in a booklet in dialogue with the music on the mixtapes bring up the many layers of reuse that form part of making music. It is a contribution to think along with the CC4r about the ethics and politics of reuse, through music. Each story engages with (and sometimes provides a possible answer to) one of the following questions:

How to collectively resist appropriation outside legal frameworks?

What type of reuse is the indiscriminate and automated one brought on by machine-processes? Why and how to take collective stances towards it?

Can reuse without consent of “original authors” happen in a response-able and critically implicated manner?

How does something stereotypical, offensive and mercenary get turned into something empowering and radical, and vice versa?

The booklet is distributed along the lines of CC4r and can be downloaded HERE

The mixtapes are bootleg copies in slow hand-to-hand pick-up circulation. If you would like to receive the tape and booklet, do write us an email, and we’ll put it in our or a friend’s bag, when a trip to your destination is in the schedule!

(Resistance)

A1 The Aztec Mystic—Jaguar (6.38)

A2 Type—Jaguar (Original Covered Version) (6.37)

A3 The Aztec Mystic—Jaguar (Mad Mike Remix) (4.21)

(Recursion)

AA1 Archspire—Involuntary Doppelganger (3.46)

AA2 Dadabots—Relentless Doppelganger (as long as YouTube allows)

(Relation)

B1 COOL FOR YOU—STRATEGICALLY ADAPTABLE (3.17)

B2 COOL FOR YOU—SEEING DIFFICULTIES (1.58)

B3 COOL FOR YOU—SHAME/HUMILIATION (2.08)

B4 COOL FOR YOU—STABILIZED, YES! (2.40)

B5 COOL FOR YOU—SHE WHOSE BLOOD (3.24)

B6 Sacred Harp Convention 1959—#112 The Last Words of Copernicus (1.41)

B7 Sacred Harp Convention 1959—#215 New Topia (2.00)

(Recast)

BB1 Bert Weedon—Apache (~0.30)

BB2 The Shadows—Apache (~0.30)

BB3 Jorgen Ingmann—Apache (~0.30)

BB4 The Ventures—Apache (~0.30)

BB5 Davie Allan and the Arrows—Apache (~0.30)

BB6 The Incredible Bongo Band—Apache (~0.60)

BB7 The Adventures Of Grandmaster Flash On The Wheels Of Steel (~0.30)

BB8 West Street Mob—Break Dance—Electric Boogie (~0.30)

BB9 Sugarhill Gang—Apache (~0.30)

BB10 Missy Elliot—We Run This (~0.30)

BB11 TLC—Hat 2 Da Back (~0.30)

BB12 Goldie—Inner City Life (~0.30)

BB13 FSOL—We Have Explosives Remix (~0.30)

BB14 Aphex Twin—Heliosphan (~0.30)

BB15 The Roots–Thought At Work (~0.30)

BB16 Scooter—Apache (~0.30)

BB17 Soundmurderer and SK1—Call da Police (~0.30)

BB18 Rage Against The Machine—Renegades of Funk (~0.30)

BB19 Amy Winehouse—In My Bed (~0.30)

BB20 Bizzy B—2099 dub (~0.30)

BB21 Jahba—Bush (~0.30)

BB22 Action bronson—Mofongo (~0.30)

BB23 NAS—Made you look (~0.30)

BB24 DJ Scud & Christoph Fringeli—Something Violent (~0.30)

BB25 Night Tapes—Humans (~0.30)

Dadabots is a collective of two developers/music lovers, who work in software and in the artificial intelligence field.1 Relentless doppelgänger is an infinite stream of sound generated by an AI model they trained and released on YouTube as a live stream. This stream of sound is produced by sampling the band Archspire, in the “technical death metal” genre, somehow picking up on its “anti-human” aesthetic. The AI sound production, containing many unrecognisable sounds, glitch breaks, etc., seems to align with the vision of the music genre that it’s taking from, which already uses growling as a singing technique, stop-and-go and extremely tight drumming.

For this neural network, Dadabots reused a technique called sampleRNN, made for voice synthesis, which is able to generate words by analysing human voice at the level of micro-samples of a few milliseconds, and to predict what microsound follows.2 In applying the technique to music, Dadabots didn’t ask for permission from the musicians they sampled, taking advantage of the undefined area of copyright law that currently surrounds the use of AI. In their words, it turns out to be a good excuse to get in touch with bands they like, asking for permission afterwards. The collective has a website to share their project, in which they display an unusual awareness and openness about the practical-ethical questions of AI methods and tools, such as “should machine learning be decolonised?”, including in their FAQs.

Dadabots are very explicit in underlining the issues with the idea of “autonomous” artificial intelligence, a problem they see as related to the potential legal autonomy of AI, projecting an even worse scenario than what happened with making corporations legal entities. They describe the risk of a shift of responsibilities, in the same way as the one that happened from people to companies, which enabled the companies to do all sorts of shitty things and that could repeat even more problematically when shifting from people to AI.

Dadabots’ hypothesis is that copyright questions will be a “foot in the door”, giving AI the status of “creator”, producing AI as a legal persona.

“Apache” is a song with a layered story, a reminder of how unpredictable paths a song can take when recording supports come in: with empty or problematic backgrounds, (parts of) this song became a source for empowering and meaningful music. Its origin is not that important, and it kinda sucks: the original song was written in 1960 by Bert Weedon, “inspired” by American Western movies and their caricature of the relations between Native Americans and Settlers.3 It is then covered by a band called The Shadows, and has medium success in the UK, and then in Denmark by Jorgen Ingmann, the covers take a “Hawaiian” twist, and the song becomes a hit for the first time. A few other “surf versions” follow, but then this cover series dies out.

“Apache” reappears in 1972, retaken by The Incredible Bongo Band, formed for writing the soundtrack of the B-movie The Thing with Two Heads, a blaxploitation-science-fiction-comedy film. Their cover of the song introduces a long-hand percussions and drums solo, making it perfect reuse material during the first emergence of Hip Hop culture in the early 1970s. DJs would search for obscure records in crates at record shops, looking for beats you could dance to at block parties. So DJ Kool Herc finds the record of The Incredible Bongo Band, which, thanks to its long drum break, he can use endlessly as a background for breakdancing in his merry-go-round technique that loops these breaks on two of the same records. As DJs would usually do back then, he would hide the label of the record at performances, to gain a certain exclusivity and create his sound signature. Despite his precautions, this song and its drums and percussions breaks is such a success that it becomes extremely famous in the Hip Hop scene, to the point that new tracks are created that are explicitly sampling the song. So, it is another “Apache” song from the first commercial Hip Hop act The Sugar Hill Gang that goes mainstream. This band is put together by the label Sugar Hill, the first to capitalise on underground Hip Hop, and they record a fully messed-up version, with more caricatures of Native Americans and samples from The Incredible Bongo Band.

The song has become a fundamental element in Hip Hop, and with the explosive growth of the movement, companies are making records for early sound producers: they sell breaks records, compiling samples ready to be used, among which “Apache” is a must. With the digitalisation of sound in the 1980s and 1990s, the music industry adapts these products to digital samples packs. By being in most of these sample packs, “Apache” ends up being used by thousands and thousands of music producers, becoming such a classic drums sample that it sort of plays the role of a very discreet musicians’ meme. The first electronic music producers start from the same sample packs in the 1990s, so Breakbeat, Jungle, Drum and Bass, Breakcore, all continued making the drums break from The Incredible Bongo Band ubiquitous.

In this story the copyright question isn’t really coming in, no court cases are connected to the massive reuse of this sample, but these opportunistic reuses made it a key element in the social and cultural movement of Hip Hop. There is no one origin of “Apache”, or there are many, and in any case, they are all messy and show how every music project starts already implicated in the modes of capitalist cultural production.

In her article “Complicating Critique”, artist and musician Vika Kirchenbauer shares that her practice has been oriented by the idea of “sampling as critique”.4

Her work in COOL FOR YOU takes on a decolonial angle, as she chose to use recordings of the Sacred Harp, a choir practice from the South of the USA that became diffused around the middle of the 1800s as part of the colonisation process, therefore implicated in slavery and the extermination of American natives. Imported from British settlers, this choir practice was performed by amateurs, mainly white Christians, who sung exclusively for their community as a form of social-religious gathering and bonding moment.

Even though she does not mention the source recordings used, Kirchenbauer seem to sample the recordings of ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax, who had access to a Sacred Harp convention in his function of archivist of American folk music in the 1950s. Due to the trust accorded to Lomax by the members of this community, he could record a form of music that was not meant for a public.

In her article, Kirchenbauer discusses the intellectual and relational placement of her practice, starting with her intention to take the recordings of the Sacred Harp beyond the consent of those recorded, and make new pieces as a way of working on the entanglement of music and colonisation. Describing what happened in making this work, she mentions that by getting close to the material, instead of exercising a mode of critique that was detached and distancing from its object, she became more and more entangled with the sources. Reflecting on how in which critique is implicated in its object, she shares how she has been touched by something she wanted to critique in the first place, through the process of sampling and listening to these sounds intimately.

The combination of her sound and writing work is rich and complex, as Kirchenbauer navigates questions of appropriation and copyright and legitimacy in an uncharted manner, through implication and affect.

Knights of the Jaguar is an EP by DJ Rolando, a member of Underground Resistance, a collective and a record label started by black musicians at the end of the 1980s in Detroit. UR are fundamental in the emergence of the techno scene, producing records and setting up events with DIY means and through self-organisation. They saw music as a way of fighting against society and its oppression and were explicitly anti-major labels and the music industry.

DJ Rolando, aka The Aztec Mystic, who comes from the Latino community of Detroit, enters the collective in the 1990s and in 1999 releases Knights of the Jaguar, which contains a track named “Jaguar”. The track is very successful in underground techno circles, to the point of receiving attention from the mainstream.

Early 2000, Underground Resistance is informed that Sony BMG (the branch of the firm in Germany) circulates a promo release of a track called “Jaguar”, a sound-by-sound commercial rip-off of DJ Rolando’s track, without crediting anyone. UR takes it as a declaration of war, rather than a clear case of cultural appropriation. They choose not to go for the legal way for two main reasons: first of all, Sony has infinite financial resources to handle a legal procedure, but most of all, they don’t believe in the justice services from the government, nor in copyright as a means of regulating cultural production.5

So, they take it on with DIY means and self-organise the resistance through their online and offline communication channels with the support of the techno community and beyond, calling for different modes of direct actions. In different places in the USA and elsewhere, UR supporters pressure local shops not to take on Sony’s release, or hide or steal copies in shops, and circulate the story further.

Another strategy brought on by UR was releasing the album The Revenge of the Jaguar, composed by remixes of the original track by UR artists. Using the ongoing hype around the story, they produced the remix record in the UK, to bring their own versions of the track to the European market. After all this, Sony offers to pay the rights and attributions to the author of the song, which the collective refuse. They stick to their approach, so Sony finally cancels the release and buries its shitty version.

Notes

The stories in the booklet have been written thanks to the following articles:

- Dadabots. “FAQ”. dadabots.com. ↑

- Carr, CJ and Zukowski, Zack. “Generating Albums with SampleRNN to Imitate Metal, Rock, and Punk Bands”. In Proceedings of the 6th International Workshop on Musical Metacreation. 2018. ↑

- Matos, Michaelangelo. “All Roads Lead to ‘Apache’”. In Listen Again: A Momentary History of Pop Music. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. 2007. ↑

- Kirchenbauer, Vika. “Complicating Critique”. In Works, Scripts, Essays 2012–2022. Milan: Mousse Publishing. 2022. ↑

- McCutcheon, Mark A. “Techno, Frankenstein and Copyright”. Popular Music. vol. 26. no. 2. 2007. ↑

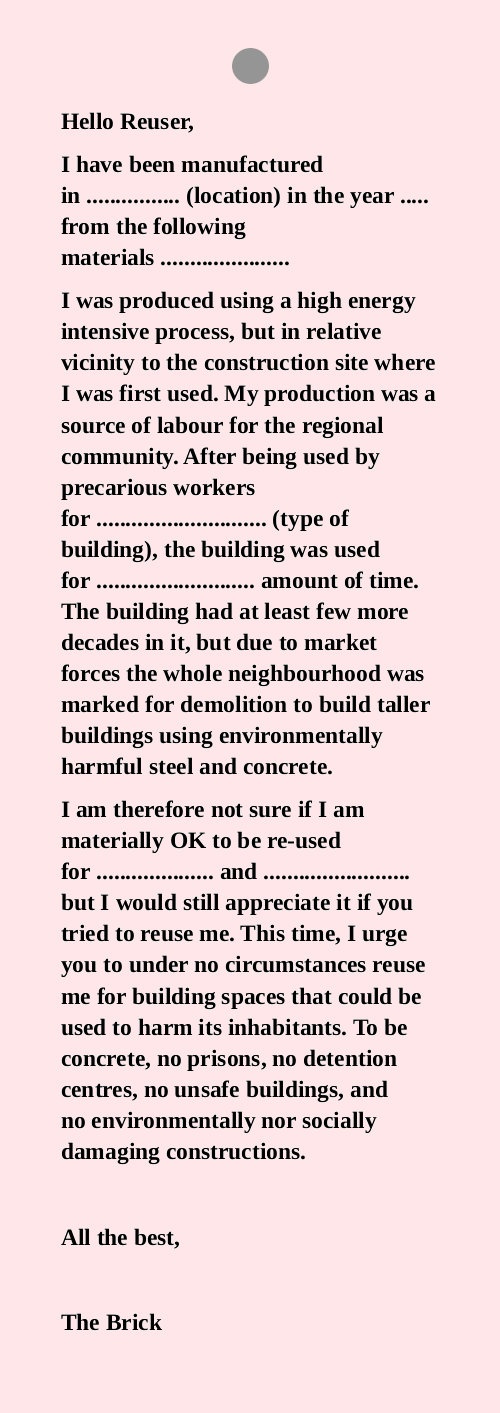

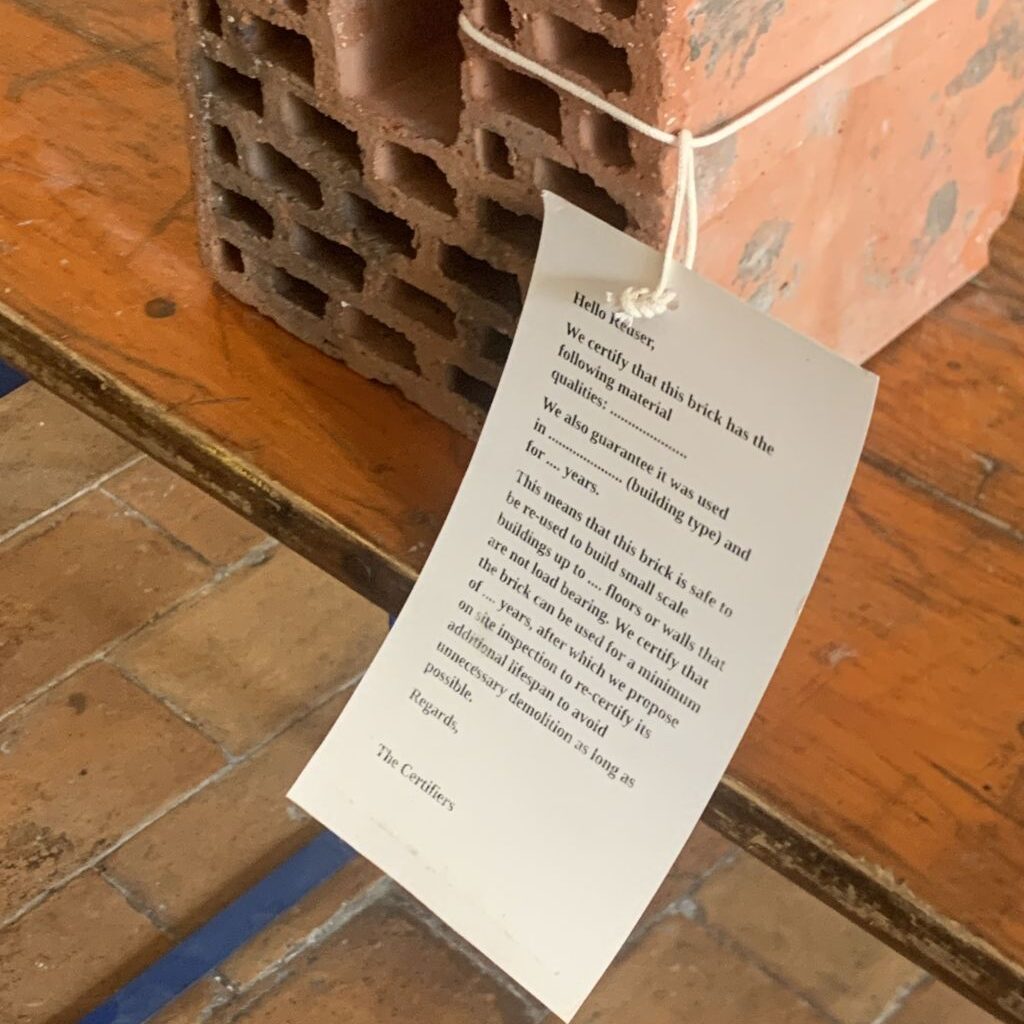

Prompt: Certifying Bricks

This prompt emerged during a conversation with author, friend and architect Dubravka Sekulić. She proposed us to think with the certification processes of recycling materials, and more specifically with bricks, as a way of asking questions about agencies, processes, relations and positions involved in reuse.

Everyone speaks about reuse all the time but what does it actually mean concretely? What relations does it set up and which ones does it transform?

Download labels for printing (PDF)

Hello Reuser,

I have been manufactured in ……………. (location) in the year ……………….. from the following materials ……………………….

I was produced using a high-energy-intensive process, but in relative vicinity to the construction site where I was first used. My production was a source of labour for the regional community. After being used by precarious workers for ……………………….. (type of building), the building was used for ……………………… amount of time. The building had at least few more decades in it, but due to market forces the whole neighbourhood was marked for demolition to build taller buildings using environmentally harmful steel and concrete.

I am therefore not sure if I am materially OK to be reused for ……………….. and ……………………. but I would still appreciate it if you tried to reuse me. This time, I urge you to under no circumstances reuse me for building spaces that could be used to harm its inhabitants. To be concrete, no prisons, no detention centres, no unsafe buildings and no environmentally nor socially damaging constructions.

All the best,

The Brick

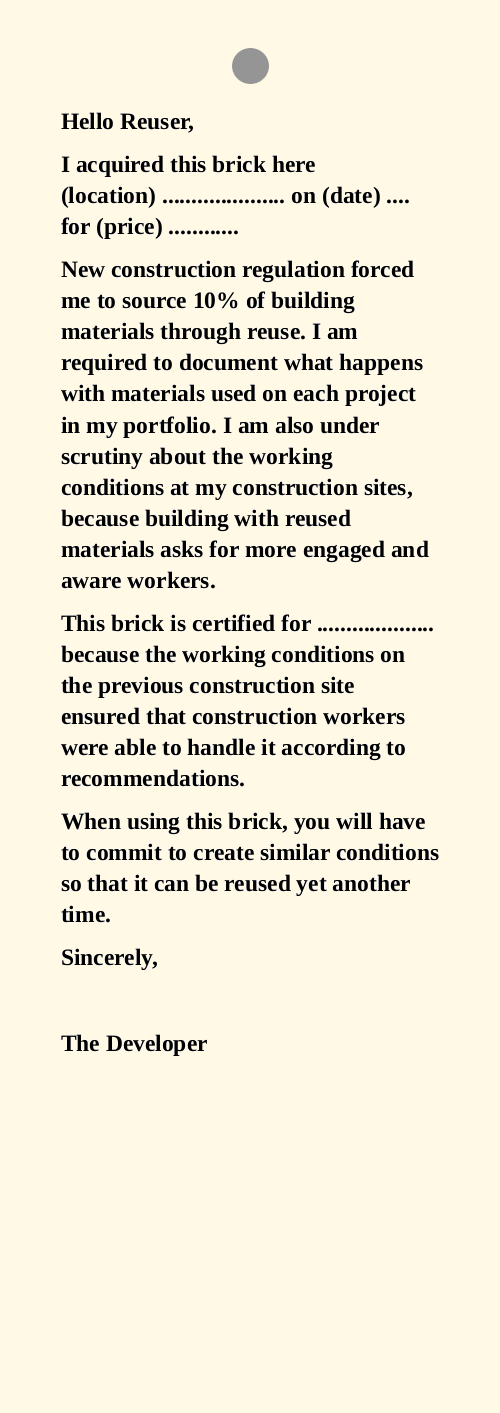

Hello Reuser,

I acquired this brick here (location) ………………… on (date) ……………… for (price) …………

New construction regulation forced me to source 10% of building materials through reuse. I am required to document what happens with materials used on each project in my portfolio. I am also under scrutiny about the working conditions at my construction sites, because building with reused materials asks for more engaged and aware workers.

This brick is certified for ……………….. because the working conditions on the previous construction site ensured that construction workers were able to handle it according to recommendations.

When using this brick, you will have to commit to create similar conditions so that it can be reused yet another time.

Sincerely,

The Developer

Hello Reuser,

The developer acquired this brick here (location) ………………… on (date) ……………… for (price) ………………

I have used this brick in (location) ………………… We continue to fight for working conditions that are safe every day and on each construction site we work on.

When I previously encountered this brick, I was working under fair and safe working condition that enabled me to install it in a way that ensures it can be used in the future.

Use this brick in solidarity with our fight for better conditions to make sure bricks can be reused in the future.

Best wishes,

The Construction Worker

Hello Reuser,

We certify that this brick has the following material qualities: …………………

We also guarantee it was used in ………………… (building type) and for ………… years.

This means that this brick is safe to be reused to build small-scale buildings up to …. floors or walls that are not loadbearing. We certify that the brick can be used for a minimum of …. years, after which we propose on-site inspection to re-certify its additional lifespan to avoid unnecessary demolition for as long as possible.

Regards,

The Certifiers

Certifying bricks: A conversation

Dubravka Sekulić (DS): When you asked me to think about reuse in culture, I started to think about this in relation to the growing conversation about reuse in built environments, as a result of finally acknowledging the complicity of architecture and the construction industry in the climate collapse. The industry started to turn to reuse, realising that the practice of continuously relying on newly extracted materials to fuel the never-ending cycle of demolition and construction of new spaces and using new materials is not necessarily compatible with sustainability and the big fight against climate change it was supposedly committed to…

Of course, the reuse of materials for construction is nothing new. In London, where we are talking, there is a long history of reusing bricks, not just in small-scale projects, such as the construction of single-family houses, but also in large housing estates. However, beside all goodwill that is starting to appear in the construction industry to reuse, there are a lot of hurdles, especially when it comes to insurance and material standards. Material standards and building codes, which have historically been developed to protect people from buildings collapsing on their heads or incinerating them, have to evolve and change to allow for reuse but also to offer robust protections. This is maybe not that bad, as the trust in material specifications is already deeply eroded after recent construction scandals, and the Grenfell Fire Inquiry revealed the scale of corporate manipulation that burdens the field. But I digress.

What is good is that in times of crisis, requirements push to start reusing materials. This has opened up a whole new space, which is now being transformed and thought through by way of the question: what does it mean to reuse materials? What are the procedures you have to follow—not only in order to secure access to this material so that you can reuse it and make sure that not everything is thrown into a landfill? But also to get insurance: how do you get a certificate that declares that the used steel beam will behave as expected under certain conditions?

Ideally when you buy any construction material, a pile of bricks or cladding material, you get a certificate, which tells you, for example, how that material behaves under conditions of fire, what its loadbearing capacities are, how it should be installed so that it behaves within the specified parameters… in order to guarantee that it will perform as expected. This ensures that when all diverse building components are installed, the building will comply to all health and safety regulations.

The more industry shifts to reuse, the issue to solve will be how to combine differently standardised elements and how to understand overall risks. The routine of specifying materials becomes the skill of design in bringing these different elements together. You’re not specifying “make me this amount of this, fit new steel beams this way”, but you are kind of combining those that exist, even though these will often be standardised profiles.

I am interested in how you then write such a certificate. Can this new type of specification include not just the history of origin but also the instructions of how to reuse something? You can’t assume that they can be reused in exactly the same way that brand-new ones can be used. So, you have to provide a different kind of description. There are further issues of scale, storage and material cycles that are connected to this process. This transformation is slowly underway, and a number of cities, London for example, already condition the issuing of building permits on reuse. This process shifts attitudes towards how materials are put into words, which also shifts attitudes towards how you design, because you have to then think beyond “I’m designing something to look as if it didn’t exist before” or “design with a spreadsheet that makes most money for those who are financing”, but you’re also here to enrich the design with materials which are there or readily available. You have to think materials in a more concrete way, and all of a sudden it becomes much more important to know what these materials did before.

Femke Snelting (FS): Do you think this material practice of reuse maps onto authorial reuse?

DS: Maybe it’s not possible to map one onto the other, but I thought it could be interesting to think these two in relation, especially because cultural reuse has been, in a way, regulated longer. What does it mean to not just use something, but to reuse it? To look into the practices of architecture and construction to see what the issues are that we are missing when we think about reuse of immaterial, intellectual content.

FS: Yes. What would it mean to have an authorial practice that already prefigures reuse in its production, in which the understanding that materials were not yours to begin with is already built into the practice that might be reused in the future?

Eva Weinmayr (EW): So, I wouldn’t go out and buy a new brick; I would take a reused brick. And that brings all the history and the conditions and the relationships implicitly with it; that’s really a nice way to connect the two.

FS: In these certificates, is there also thinking about reuse that would be restricted to certain purposes? Like… not for military use?

DS: Not that I know, but I think that’s something really interesting. For example, would it be possible to specify that if you demolish council housing that you can’t reuse the materials for a profit-making space? The issue here is that most new constructions are for profit, and that the industry has to be incentivised to shift from new to reused materials, as they tend to shrink profit margins because they require different storage, specifications, detailing… The whole process of how buildings are designed and constructed has to be at least tweaked by this shift. Certification becomes even more important. I think the certificate to certain degree assumes that you don’t need contact between those who used the material before and those who are going to reuse it. It has to be something that one can trust. In this culture of reuse that we are thinking about, mistrust is more on the side of the latter, of the reuser.

FS: I think this is not so different from how Free Culture licences function, and why we are interested in them as tools for making the conditions of reuse explicit.

DS: But aren’t there many things that are being reused in cultural contexts that are not necessarily under Creative Commons? I think what I found interesting when I first encountered Creative Commons, is that it made one really ask oneself questions that you don’t necessarily ask about your work. Ask yourself: under which conditions I want this work to be reused inevitably makes your ask also under which conditions you are actually making this work to begin with? At least for me it also made me think… is any work ever individual to begin with…? Under which conditions is my work mine to determine then also how it exists in the world? Who can reuse it? What can I reuse? I think it made everyone more literate in understanding any conditions, not just fair. What are the questions and issues?

The analogy to what is now happening in art in architecture, is that suddenly people are much more concerned with how materials they specify are actually produced. Under which labour conditions? How far they have travelled? Can I change some of these conditions by how I specify materials? Do I need to use something that is produced here and then has to be shipped to there, or can I use…?

How do you frame these conditions… how do you work with different materials and across different times and geographies? Or what groups are connected and what allows those who do the negotiating to understand all the possible implications and how will they be able to interpret these relations?

London, June 2023

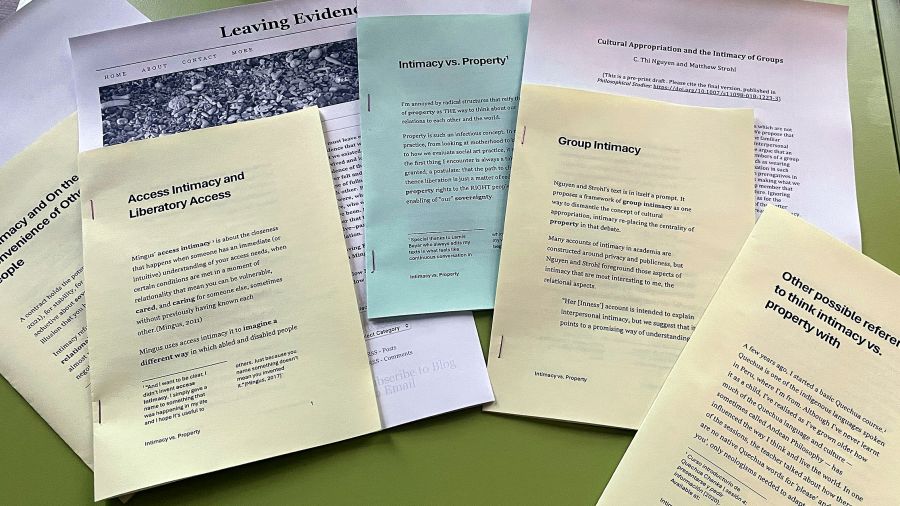

Prompt: Intimacy vs. Property

This prompt has been contributed by Andrea Francke who proposes to revisit the “infectious concepts” of property and sovereignty. She writes, “I’m annoyed by radical structures that reify the idea of property as the way to think about our relations to each other and the world.” Instead, she calls for the courage to pay attention to the actual ways in which we exist with each other, what she calls “the intimacy of interdependency”.

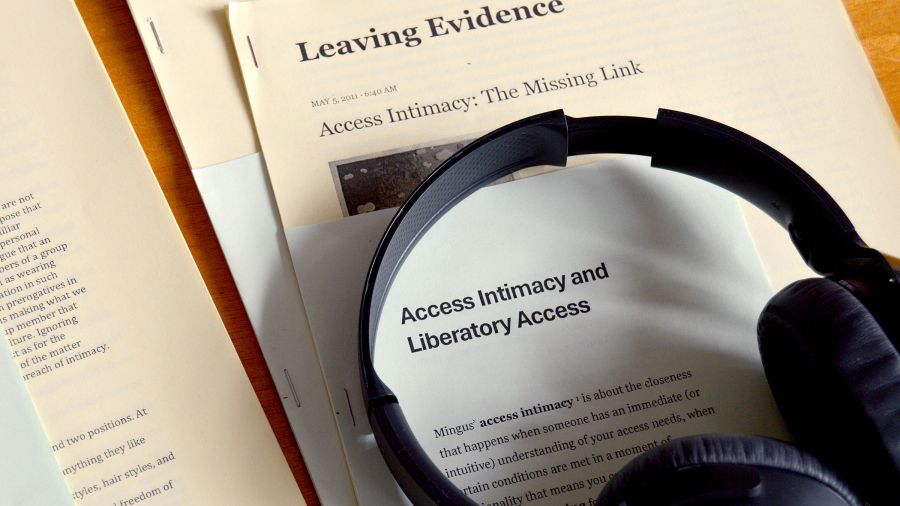

With the help of a selection of texts, from C. Thi Nguyen and Matthew Strohl to Lauren Berlant and Mia Mingus, Andrea provides different entry points to thinking about the shift from property to intimacy. For those who have difficulties in engaging with long texts, she prepared short introductions summarising the texts’ main ideas, as well as her rationale for selecting them. She also sent audio recordings of her prompt with spoken word for ease of access.

→ See Prompt: Real-life Examples

Intimacy vs. Property1

Listen to Andrea

I’m annoyed by radical structures that reify the idea of property as the way to think about our relations to each other and the world. Property is such an infectious concept. In my practice, from looking at motherhood to book piracy and how we evaluate social art practice, it seems that the first thing I encounter is always a taken-for-granted, a postulate, that the path to change and thence liberation is just a matter of redistributing property rights to the right people and the enabling of “our” sovereignty.

I see this as a trap. One that makes it almost impossible to imagine a different way to think about ourselves and the world. We are terrified of what would happen if we didn’t own the things we care for.

But I think that it is the “we care for” that matters. That there is a different form of relationality that can only exist once we refuse to play the property and sovereignty game and pay attention to the actual ways in which we exist with each other. I call this the “intimacy of interdependency”.

In this prompt, I propose that the “Collective Conditions for Reuse” fall into the same trap. That in its attempts to solve the “problem” of intersectionality and power imbalances in systems like Copy Left or Creative Commons, it reifies the all-too-well established (mis)conception that property is the only way in which we can think ourselves and the world, expanding the market into every sphere of our lives—particularly those spheres which specifically sought to separate themselves from the market. That it attempts to improve what needs to be dismantled.2

This is a prompt to imagine that we already have a much more sophisticated and interesting way to relate to what we all bring into being in the world. We do. We just need to stop making frameworks that try to make it legible and accessible to systems of power.

This prompt gestures towards a series of texts and notes that offer different definitions, doubts/limitations, and ways to use intimacy to think together about what could exist in place of the idea of intellectual property. I’m fully aware that these ways require profound changes in how we organise the world. I don’t have a solution. I just want us to imagine better.

Andrea Francke

London, 4th of April 2024

1 Group Intimacy

Listen to Andrea

C. Thi Nguyen and Matthew Strohl’s text is a prompt itself. It proposes a framework of group intimacy as one way to dismantle the concept of cultural appropriation, intimacy re-placing the centrality of property in that debate. Many accounts of intimacy in academia are constructed around privacy and publicness, but Nguyen and Strohl foreground those aspects of intimacy that are most interesting to me, the relational aspects.

Her [Inness’s] account is intended to explain interpersonal intimacy, but we suggest that it points to a promising way of understanding group intimacy.3 For Inness, what makes an act intimate is that it expresses an agent’s loving, liking or caring for another person and thereby has special meaning and value for the agent. We propose that, in the case of larger groups, what makes a practice intimate is that it functions to embody or promote a sense of common identity and group connection among participants in the practice, and thereby renders it meaningful and valuable to these participants.4

Once we move away from property and into relationality, ideas of care, affection and maintenance gain in importance. If the process of how we use stuff, including ideas and the expression of those ideas by others, is concerned with if and how we are extracting or contributing—who are we inconveniencing? How are we contributing to our communities or despoiling them? How are we inconvenienced?—and if those effects are constantly negotiated and re-considered, then how does a licence facilitate or obscure our relation to those inconveniences and to others?

But, crucially, the intimacy account does not yield objective determinations about who can participate in an intimate practice. Intimacy is flexible—relations of intimacy can be extended, outsiders can be granted temporary or long-term insider status, insiders can be exiled, and boundaries can be re-drawn. Furthermore, notice the order of operations with intimacy. It is not the case that a relationship is first established as intimate, and only then can the participants in the relationship engage in intimate acts. Engaging in intimate acts is what constitutes an intimate relationship. […] Intimate groups can sometimes self-constitute through intimate practices—they can come into existence as a result of self-identification, valuation, and mutual engagement through intimate practices.5

2 On Intimacy and On the Inconvenience of Other People

Listen to Andrea

A contract holds the potential for clarity for stability, for a resolution.6 What is so seductive about sovereignty and property is the illusion that you have a firm ground to stand on.7 Intimacy refuses the stability of clarity because relationality (that is interdependence) is almost never stable. Intimacy is always already negotiated between subjects, at a bodily scale. The way you related to someone’s work yesterday may no longer be quite right today, and vice-versa. When you realise someone is using your work in a way that you don’t agree with, or in a way that erases you, or when you realise you’ve used someone’s work in a way that has harmed them or annoyed them, you feel it in your body. That’s what I want to hold onto. To refuse the creation of a “neutral” admin infrastructure that takes the awkwardness out.8

“I didn’t think it would turn out this way” is the secret epitaph of intimacy. To intimate is to communicate with the sparest of signs and gestures, and at its root intimacy has the quality of eloquence and brevity. But intimacy also involves an aspiration for a narrative about something shared, a story about both oneself and others that will turn out in a particular way. 9

My favourite part of Lauren Berlant’s text is the acknowledgement of how terrifying intimacy can be, how much can and will go wrong, how much needs to be constantly renegotiated.10

There, and here, the commons concept serves as a preserve for an optimistic attachment to recaptioning the potential for collective nonsovereignty and as a register for the gatekeeping and surveillance that organises still so many collective pleasures. So, if the commons claim sounds like an incontestably positive aim, I think of it more as a tool, and often a weapon, for unlearning the world, which is key to not reproducing it.11

3 Access Intimacy and Liberatory Access

Listen to Andrea

Maria Mingus’s access intimacy is about the closeness that happens when someone has an immediate (or intuitive) understanding of your access needs,12 when certain conditions are met in a moment of relationality that means you can be vulnerable, cared for, and caring for someone else, sometimes without previously having known each other.13 Mingus uses access intimacy to imagine a different way in which abled and disabled people can imagine a different future, one that cannot be brought into being by policy, bureaucracy or design. It’s a call for a political re-organisation of the world around interdependence and away from ideas of sovereignty.

Liberatory access gets us closer to the world we want and ache for, rather than simply reinforcing the status quo. It lives in the now and the future. There is no liberatory access without access intimacy, and in fact, access intimacy is one of the main criteria for liberatory access. Liberatory access understands addressing inaccessibility and ableism as an opportunity for building deeper relationships with each other, realigning ourselves with our values and what matters most to us, and challenging oppression. Liberatory access calls upon us to create different values for accessibility than we have historically had. It demands that the responsibility for access shifts from being an individual responsibility to a collective responsibility. That access shifts from being silencing to freeing; from being isolating to connecting; from hidden and invisible to visible; from burdensome to valuable; from a resentful obligation to an opportunity; from shameful to powerful; from ridged to creative. It’s the “good” kind of access, the moments when we are pleasantly surprised and feel seen. It is a way of doing access that transforms both our “today” and our “tomorrow.” In this way, liberatory access both resists against the world we don’t want and actively builds the world we do want.14

I propose we think about intimacy in an abolitionist way. I know that we live in a world that is mediated by laws, contracts and infrastructures built upon and which consolidate the idea of property (and rentiers). But I propose that we should imagine and practice a different way of being that is invested in relations over property.

We are too solely invested in the idea that the way to solve issues of labour and distribution, and even equality, is to multiply access to property rights.

4 Other possible references to think intimacy vs. property with

Listen to Andrea

A few years ago, I started a basic Quechua course.15 Quechua is one of the indigenous languages spoken in Peru, where I’m from. Although I’ve never learnt it as a child, I’ve realised as I’ve grown older how much of the Quechua language and culture—sometimes called Andean Philosophy—has influenced the way I think and live the world. In one of the sessions, the teacher talked about how there are no native Quechua words for “please” and “thank you”, only neologisms needed to adapt the language to a European framework. She explained how you don’t need the words for “please” and “thank you” because those are just words that allowed Europeans not to act.

On the other hand, she explained, if you are part of a Quechua community, you will keep an eye on what is needed, and then just do it.16 You won’t need a “please”, and you won’t expect a “thank you”. At some point, if you need help, there will be other people around you paying attention and help will happen.

That relation between attention, care, and being part of a (or many) community(ies) made so much sense to me. This is also part of an understanding of the world in which the non-human is very present. This relation of intimacy that allows one to perceive when one is needed and act, exists also in relation to mountains, animals, places, etc. It made me think about my relation to other people’s work, how I share things—including things that aren’t mine, to how I put things in the world and how accessible I construct them so people can take them apart and use them.

There is another approach that I wanted to include, but I just didn’t have the time. In The Logic of Care, Annemarie Mol looks at the relationships between the ill and their carers.17 Mol proposes that those relations follow a different logic that refuses the logic of choice (which either follows consumer or citizenship logics) but instead is constructed collaboratively through continued attunement.

Notes

- Special thanks to Lamis Bayar who always edits my texts in what feels like continuous conversation. ↑

- Thank you to Daniel Rourke for introducing me to this quote from Boris Groys:

“I hope that the political function of these two divergent and even contradictory notions of aestheticization—artistic aestheticization and design aestheticization—has now become more clear. Design wants to change reality, the status quo—it wants to improve reality, to make it more attractive, better to use. Art seems to accept reality as it is, to accept the status quo. But art accepts the status quo as dysfunctional, as already failed—that is, from the revolutionary, or even postrevolutionary, perspective. Contemporary art puts our contemporaneity into art museums because it does not believe in the stability of the present conditions of our existence—to such a degree that contemporary art does not even try to improve these conditions. By defunctionalizing the status quo, art prefigures its coming revolutionary overturn.”

Groys, Boris. “On Art Activism”. e-flux Journal. no. 56. 2014. ↑ - Inness, Julie C. Privacy, Intimacy, and Isolation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996. As referred to in Nguyen, C. Thi and Strohl, Matthew. “Cultural Appropriation and the Intimacy of Groups”. Philosophical Studies, vol. 176, no. 4, 1 April 2019, pp. 981–1002.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-018-1223-3. ↑ - Nguyen and Strohl, “Cultural Appropriation and the Intimacy of Groups”, p. 12.

[Download pre-print PDF] ↑ - Nguyen and Strohl, “Cultural Appropriation and the Intimacy of Groups”, p. 16. ↑

- Nguyen, C. Thi. “The Seductions of Clarity”. Royal Institute of Philosophy Supplement, no. 89, 2021, pp. 227–55.

Download pre-print. ↑ - “As I argue in the introduction, my view is that sovereignty is at root a defense against occupation or dispossession, which is why it’s become central to antagonisms about jurisdiction, and not anything like a natural right or natural state.” Berlant, Lauren. On the Inconvenience of Other People. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. 2022. p. 80 (“Writing matters!”) ↑

- For an expanded definition of awkwardness, listen to Francke, Andrea and De Kersaint Giraudeau, Matthew.

“Bad Vibes Club at CCA—The Rise of the Awkward Turtle”. 2016. ↑ - Berlant, Lauren. “Intimacy: A Special Issue”. Critical Inquiry, vol. 24, no. 2, 1998, p. 282. ↑

- “It shows how some thinkers use the commons concept to move away from good-life fantasies that equate frictionless mess with justice and satisfaction with the absence of frustration.” Berlant, On the Inconvenience of Other People, p. 81. ↑

- Ibid., p. 80. ↑

-

“And I want to be clear, I didn’t invent access intimacy, I simply gave a name to something that was happening in my life and I hope it’s useful to others. Just because you name something doesn’t mean you invented it.” Mingus, Mia. “Access Intimacy: The Missing Link”. Leaving Evidence, 5 May 2011. ↑

- Mingus, Mia. “Access Intimacy, Interdependence and Disability Justice”. Leaving Evidence, 12 April 2017. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Curso introductorio de Quechua Chanka | sesión 4: presentarse y pedir información. 2020. ↑

- This form of attention and responsiveness sounds very similar to Mingus’s Access Intimacy. ↑

- Mol, Annemarie. The Logic of Care: Health and the Problem of Patient Choice. London: Routledge, 2008. ↑

Prompt: It’s Not a Thing

This prompt is based on a conversation with Peggy Pierrot, just after her return from an intense working period in Martinique. Peggy makes a living as intellectual worker, teacher, writer, radio host and independent researcher and is based in Brussels. We have been crossing paths for many years in the context of activities related to Free Culture and software freedom, but never directly discussed possible tensions between decolonial feminist practices of reuse and the frameworks that we have both committed to. At the end of this long conversation, Peggy reflects on translating her ideas and convictions about Free Culture to the context of the Caribbean, confronting a radically different economic reality.

Does the framework of Free Culture or Open Access make sense in a non-European context, and if not how would it need to change, to become “a thing”? Is this a matter of translation, or of transformation?

→ See: Prompt: Spaces for Discomfort – Who Will be Paying the Price

It’s Not a Thing: A Conversation

Peggy Pierrot: I was in this art school [in Martinique], where they never heard about Free Software and they were like, what the hell are you talking about? Uh, you mean that we don’t pay for the licence, right? And the way they were seeing authorship and the relation to the tools and everything was so different. I was like, OK, how do I do this? Because the context is so different. In terms of class, possibility of work, all these things.

For example, something I didn’t know before going there: all the students are obsessed with 3D, because in the Caribbean there are studios that are sub-contractors for Pixar studios and others. So, I needed to consider the level of unemployment in that context. They all use Blender, but they also use other tools. And it doesn’t make any difference to them whether you can contribute or change or adapt the software. It’s not a thing.

And then the question of economy came back in my face. I did actually talk about Free Software and the question of copyright. And no, you cannot use these images because you see, there is a copyright. But it was so far from their context that I had to kind of adapt my discourse. Because everything was different. This art school is set in a completely other context, both colonial and the Caribbean, and of course there’s a need to adjust to that. For example, all these things we do with HTML, to print or when we were talking about scripts, that doesn’t make any sense: no one cares.

There’s no publishing industry in Martinique because there are only two companies that make books and they do so in Microsoft Word, or whatever, because the market of people buying the books produced by people from Martinique or Guadeloupe in French or Creole is so narrow. One or two libraries in Paris buy everything, because they know they have the diaspora that will look for those books. One local publisher said, “sometimes I sell books in Brussels because there are these two libraries that ask for books from me.” The small artist, small publisher scene is non-existent. So is the free software or independent media scene, like the one we know here. But there are other things, of course.

So within this context, I think part of what lacks in Free Culture is trying to be in connection with people. All the things that I talk about come from where I grew up. My relation to the world has been shaped in a specific context. Which is European, even though I have ties with the West Indies. I am a European and I have a way of seeing the world that is linked to this context. And I cannot just export it as it is, I have to rethink my position in the discussion.

Now it’s not that I don’t want to do this, but it needs some adjustments and negotiations, change of expectations, that kind of stuff. And I think it’s related to what we were talking about. When you think about remodelling the Free Art Licence to be able to take into account the power relations, the different conditions and ethical questions. This is exactly what I mean.

Brussels, April 2023

Prompt: Real-life Examples

This prompt was prepared by C. Thi Nguyen, philosophy professor at University of Utah. We contacted him right after reading “Cultural Appropriation and the Intimacy of Groups”, a text that Andrea Francke (who proposed Prompt: Intimacy vs. Property) suggested us to read. In this text, which he wrote together with Matthew Strohl, C. Thi Nguyen explains the dead ends that both “universal entitlement” and “universal restrictiveness” represent when it comes to dealing with cultural appropriation.

In thinking about cultural appropriation, what I came to think was that it was bad that one of the key problems was thinking in blanket terms: that cultural appropriation was always problematic or always OK. Instead, what Matt Strohl and I came to think was that some practices had particularly powerful meanings to particular groups. They were intimate practices, practices of group solidarity, that expressed something important about belonging to a group identity. Furthermore, it mattered what a particular group licenses about a particular practice. Some groups are eager to have particular practices disseminated, other groups might want particular practices held private, sacred, or special. And it matters the social power of the group, since we have reason to particularly help to protect the cultural identity of threatened groups. (More here.)

You don’t have to think this way, and I don’t expect you to agree with us necessarily. But if you want to try, I invite you to try to approach some difficult cases thinking about respecting the wishes of the relevant group. Because in real-world cases, this turns out to be very difficult: because of the complex cascades of overlapping groups and overlapping practices. I find some of these less puzzling, and some of these more puzzling.

I apologize for the American focus of the examples, but I have tried to draw and adapt from real life examples that I know well—because the details are important.

A museum in California, as part of Asian American Heritage Month, puts on display a set of kimonos and invites museum attendees to try them on. Asian American activists protest the event as a form of cultural appropriation, and point to the runway event, below. Most of the activists were born in America and come from a variety of Asian ethnicities. There is, however, a counterprotest, by Japanese-born immigrants, who point out that kimonos are, in Japanese culture, a gift object, intentionally created to be worn by outsiders. What should the museum do?

The practice of wearing au dai—Vietnamese formal long dress—has sometimes been taken on by white Americans. Recently a French designer had a runway show in Los Angeles, in which American, mostly white and black models, walked the runway wearing au dai. This sparked a storm of protest from Asian American activists, as a particularly egregious form of cultural appropriation —especially since it was coming from a French designer. Now, Tom is getting married to Nancy in Los Angeles. Tom is a white American, Nancy is a Vietnamese American. Nancy participated in those protests. But Nancy’s Vietnamese family strongly wishes that Tom would wear an au dai at their wedding. What should they do, and why? And should it matter if any photos will be posted on Instagram?

Suppose you are a British white person, who is in love with different African textile patterns. You are aware that there have been several criticisms, by black British people, complaining that the cultural appropriation of African textile patterns is a painful kind of appropriation, especially insulting given the history of British colonization. However, you locate an online shop that sells a particularly beautiful textile. The shop’s online FAQ states that the pattern is distinctive to the shop owner’s particular village, and that the shop owner encourages everybody, no matter their racial or cultural heritage, to buy and wear this beautiful fabric. Should you purchase it, and if you do, in what contexts might you wear it?

Debates are raging inside various American Latino communities about the permissibility of non-Latino people displaying Day of the Dead decorations on their lawns and homes around the appropriate holiday. Roughly, a majority of Latino academics and cultural writers have argued that it is a problematic form of cultural appropriation, that partakes superficially in a deep cultural tradition. (The objection isn’t to, say, a non-Latino person thoughtfully participating in a Day of the Dead parade, after learning about the history. The objection is to non-Latino people randomly buying cheap Day of the Dead lawn ornaments and sticking them in their lawns with the vague thought that they look kinda cool.) And roughly, a majority of non-academic Latinos think this is fussy and dumb, and many have expressed an affection for seeing signs of their culture spread. Suppose you are not Latino, and your five-year-old sees a Day of the Dead skull at the grocery store and thinks it’s beautiful and wants to put it on your lawn. Should you? (PS: there is a similar divide over whether the correct term is “Latinx” or “Latino”, so the language of this prompt is up for similar worries.)

Many mixed-martial artists, of every racial and cultural background—especially women fighters— have started adopting the hairstyle of cornrows, tight, low braids. These are traditionally a Black hairstyle. Many Black Americans have expressed that these seem to strike them as insulting cultural appropriation. Black hairstyles have been one of the classical loci of cultural appropriation concerns. The general worry is that Black people who wear such hairstyles are subject to various forms of discrimination and bias—and often accused of being “unprofessional”. But white people who wear such styles appear “edgy” and “cool”. On the other hand, the mixed martial artists simply say that the hairstyle is maximally functional in the MMA ring, and many white MMA fighters who wear such cornrows say that they are wearing them in solidarity with their close friends, who are Black MMA fighters. How do we balance these concerns?

Prompt: Spaces for Discomfort – Honesty

We invited Winnie Soon to contribute a prompt because of their work with Lee Tzu-Tung on queering contractual hierarchies and appropriation gestures, and also their energetic participation in the Open Source publishing community through projects such as Aesthetic Programming (with Geoff Cox).1

Winnie is an artist and academic who often works with grassroots communities and precarious cultural practitioners in both Europe and Asia. They are concerned about the peer pressure that these practitioners might experience when being asked to release a work under a Free Culture or Open Access licence. The widespread expectation that openness is in everyone’s interest might prevent an honest conversation about situated conditions, and resulting anxieties, needs and desires. When we ask Winnie to say more about what they mean by “honesty”, they answer: “To be honest with how much one would like to share and what you want from it in return. If one is not happy for others to install or pick up your code and study it, perhaps you should not have the Floss licence. Or, if you would like to be contacted for every use, just state this.”

In this prompt, Winnie asks a series of questions that can help pay attention to the feelings and insecurities involved in making work public. They ask to pause for a moment and double check which are the right conditions for sharing or not sharing. Making space to feel and acknowledge potential discomfort before releasing a work, means also making the implications of reuse imaginable. Could such frank and courageous articulations of what is at stake contribute to a practice of reuse in solidarity?

How would each project consider the situatedness of conditions?

In what way the collective/individual would find discomfort when other people (re)use your work?

How would an individual wish others to (re)use?

How could we also acknowledge the power imbalance between privileges and less privileges in free and Open Source culture, in which there might be a different understanding of extractive use?

How can we be honest with ourselves and our projects?2

Notes

- See Soon, Winnie. “Forkonomy”; Soon, Winnie and Cox, Geoff. Aesthetic Programming: A Handbook of Software Studies. London: Open Humanities Press. 2020. ↑

- Soon, Winnie. Private email. ↑

Prompt: Spaces for Discomfort – Who Will Be Paying the Price?

During a public conversation at the event “First Times Do Not Exist”, friend, colleague, poet and translator Jen Hayashida discusses translating as a practice of reuse. Using a recent practice example of relay translation, a translation of a translation, Jen describes the displacements and negotiations of authorship in this process of translating Korean American writer Don Mee Choi’s translation of Korean poet Kim Hyesoon’s book Autobiography of Death into Swedish. Building on Jen’s description of a range of displacements, such as displacement of the author, displacement of the singular, displacement of the original (see Conversation with Jennifer Hayashida: Translating as a Practice of Reuse) the question comes up whether Jen could imagine forms of circulation and sharing (for this specific book) that do not rely on the framework of copyright, i.e. would not claim ownership based on originality and authorship in the same way as copyright does. Both Jen, and work session participant Ram Krishna Ranjan address the uncomfortable dilemma that copyright is a construct historically linked to colonialism, empire and racial capital. Understanding that the legal framework of copyright is still informed by colonial practices, the struggle for people in marginal spaces means to fight that framework while also having a recourse in it, since it provides some sort of legal protection, in the face “of a machine that eats everything”, as Jen says.

Can we imagine a double strategy of upholding conventional copyright for some, and start abolishing it simultaneously with and for privileged reusers? How to build solidarity around dismantling colonial frameworks such as copyright?

Jen Hayashida explains the writer’s situation:

Don Mee debuted as a Korean American writer, not writing in her first language, displaced in various ways through war. I’m super-oversimplifying this now, though, and she is not here to speak for herself. She debuts when she’s in her late forties as a person of colour in a North American literary market. With her second book, Hardly War, and then her third book, she gets widely recognised with a number of awards, including the National Book Award. And she also wins a MacArthur Fellowship, which is one of the most prestigious awards you can get in the United States. I think there’s an ethics attached to the fact that she’s a person of colour, that she works with a small press, Wave, one of the biggest small presses. To say that she would not have a legal claim to her own work in the face of an apparatus that eats everything, would, to me, be ethically problematic! To demand of a person in that position that they give up their claims to their work in the face of a machine that eats everything, is to me not necessarily more ethical.

I think that the demand to interrogate the meaning of copyright needs to be very specific, depending on the person and work at hand. It’s easy to make those sorts of broad sweeping claims of a utopian time when there is no such thing. And [the issue is] that it implies that there’s no prehistory, a history that goes beyond the question of copyright and has to do with colonialism and empire, and racial capital. And I think that those things predate, as far as I understand it, copyright. That mechanism [of copyright] is like a symptom of something, but it is not necessarily going to solve the problem. It’s unnecessary to say that it’s worth interrogating, and imagining other models, but I think what’s inscribed in it, copyright isn’t the first thing on the scene, I guess.

Ram Krishna Ranjan thanks Jen for outlining the issues:

You articulated it really well, and I understand and appreciate the dilemma. With regards to copyright, I also think that we should link it to the project of colonialism. Copyright is very much an extension of the colonisation of time and space. Now we are at a point where people in marginal spaces are responding and reclaiming time and space. So, the turn towards dismantling time and space and imagining a utopian other time for copyright to be challenged is a bit unresolved. It produces a legitimate concern: finally, when people on the margins can claim or partake in the fruits of copyright, we are thinking of dismantling it altogether. And this is why your point about the meaning of copyright as needing to be specific is very important: what is the material, and who is it attached to?

I’m also thinking of postcolonial states and societies. Often, the legal framework around ideas of property and copyright is still informed by colonial practices. And the struggle for people in marginal spaces fighting copyright is that they fight the frameworks laid down by the postcolonial state. Still, at the same time, they have to rely on that state to protect them from injustices. So, it’s a bind that they are constantly navigating and struggling with. Therefore, it’s like, I’m going to oppose copyright, but only to an extent, because I also know that if I dismantle the framework, I will be paying the price more than anybody else.

Gothenburg, October 2023

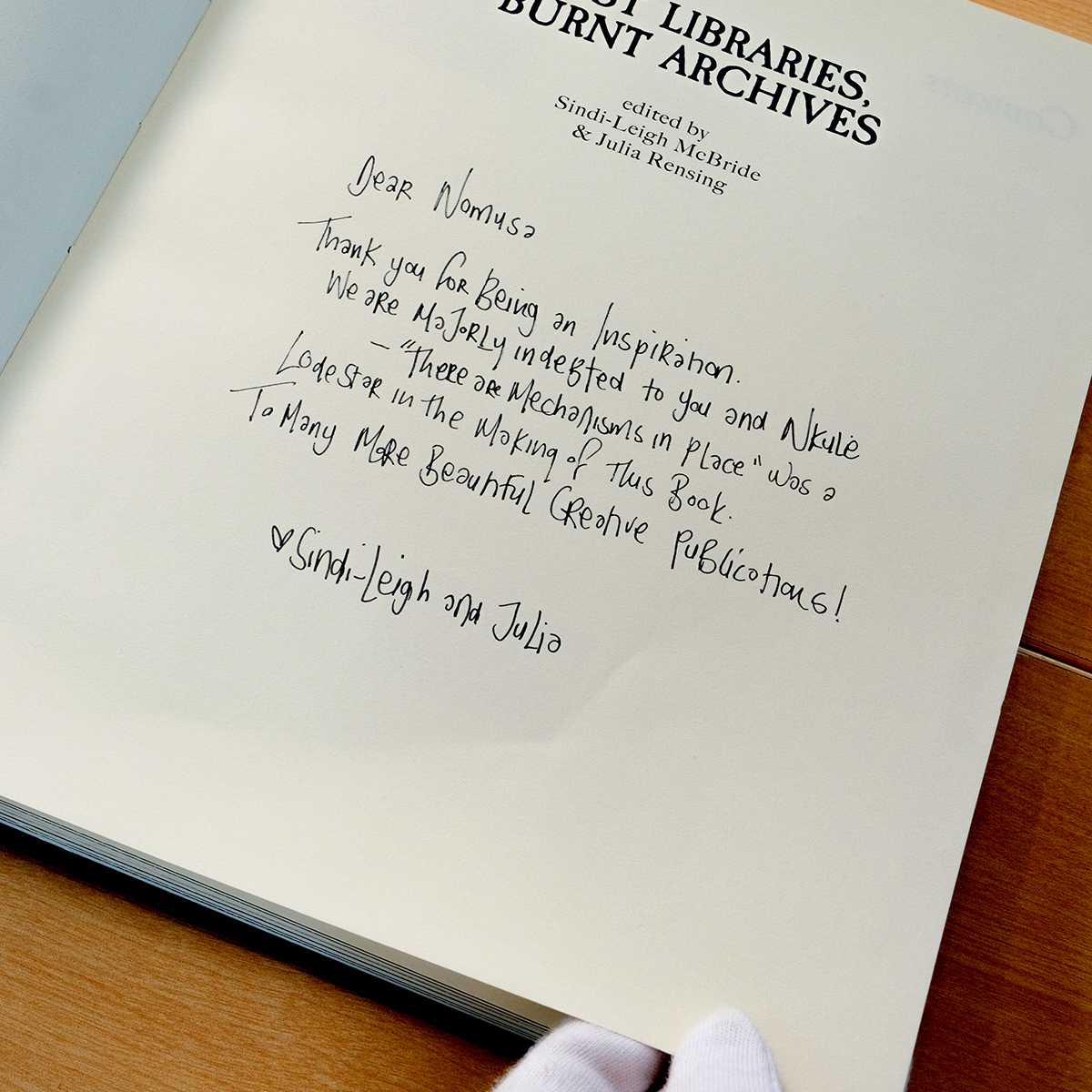

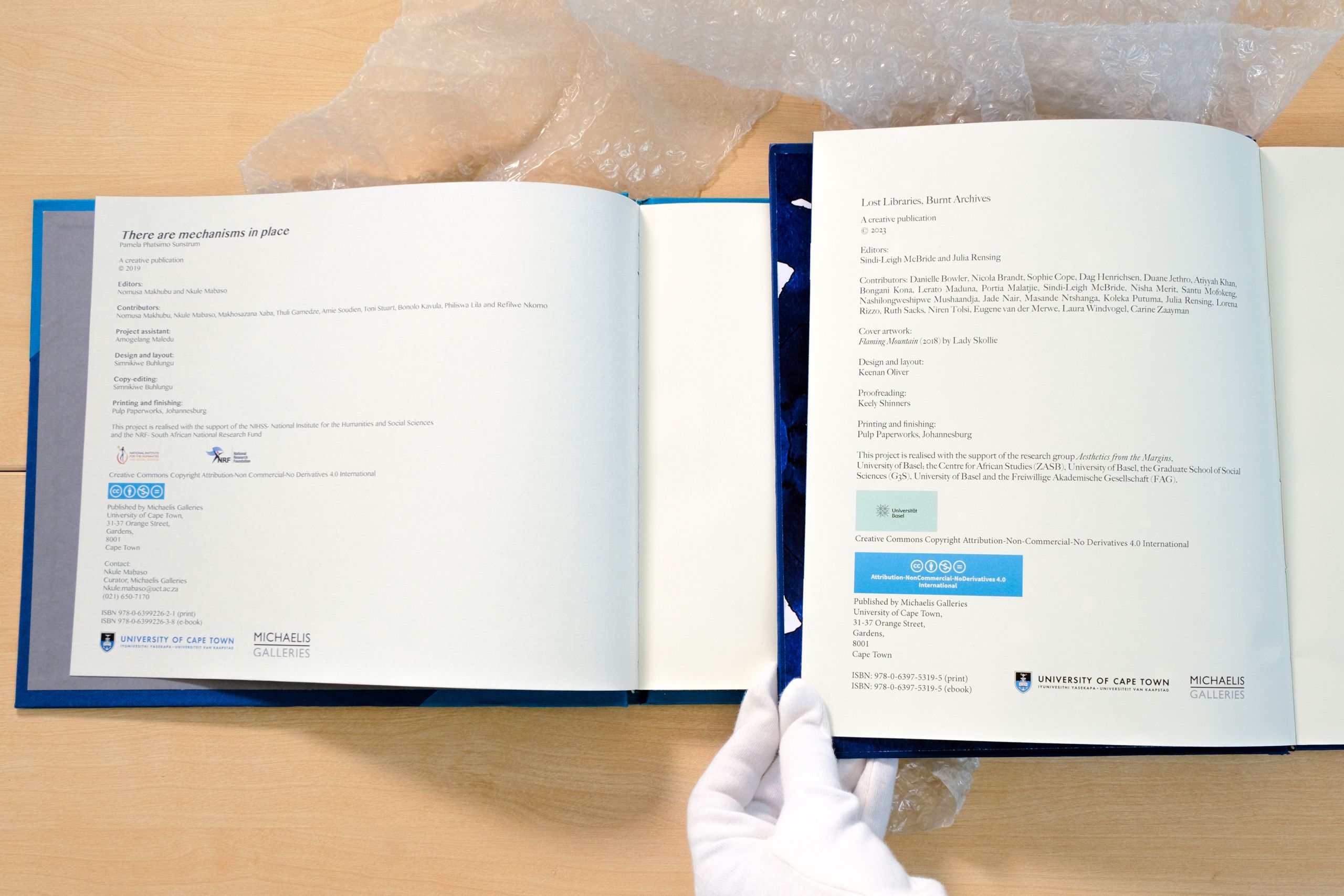

Prompt: Spaces for Discomfort – Recognition

In this prompt, which is based on the public conversation “First Times Do Not Exist” with friend, colleague, artist and curator Nkule Mabaso in Gothenburg, we ask how to deal with discomfort when encounters and inspirations are not formally acknowledged. An artistic book Nkule (co-)produced was the crucial inspiration for another peer’s work, but despite the shared understanding of the politics of recognition, this act of reuse was not formally credited.1 In this conversation, Nkule insists on the importance and the willingness to take time and be in conversation to acknowledge and sit with this space of discomfort, so the tensions can become tangible and be addressed together rather than looking for punitive gestures or corrective quick fixes. Afterwards, we edited the transcription together. Nkule decided to add several footnotes and images, continuing to map the layers of this process.

When we encounter something that catalyses our thinking, how do we make this encounter legible? How do we account for such relationships when we disclose how something comes into being? And when we have reused work without recognising one another sufficiently, what can we do?

Encounters in Practice: A Reflective Account